Yule: How the Ancient Vikings Celebrated the New Year and What Traditions We Stole from Them

Categories: Culture | History | Nations

By Pictolic https://pictolic.com/article/yule-how-the-ancient-vikings-celebrated-the-new-year-and-what-traditions-we-stole-from-them.htmlWhile the sun practically disappeared from the sky above the Arctic Circle and the night seemed endless, the Vikings prepared to celebrate Yule. This winter solstice festival marked the symbolic beginning of the new year. It was a time of fire and mead, generous sacrifices to stern gods, and sacred vows for the future. A special period when the human world came into close contact with the spirit world. Surprisingly, many of the New Year traditions we know today—from home decorations to good luck rituals—have their origins in this ancient pagan festival of the North.

The winter solstice and the longest night of the year, December 21st to 22nd, were considered a magical time in many cultures. Numerous legends, superstitions, and mysterious customs are associated with these days. Naturally, the Vikings also revered this December day. They celebrated Yule with great fanfare: for the Scandinavian peoples, it essentially replaced the modern New Year.

Scientists still can't pinpoint exactly when Yule began to be celebrated in northern Europe. It is known for certain that by the 5th century, it was already being celebrated in full swing in both Scandinavia and the British Isles. Moreover, researchers have established that the ancient Britons borrowed this holiday from their northern neighbors, who had been launching daring raids against them for centuries.

Yule first appears in historical documents in the 8th century. At that time, the chronicler Bede the Venerable, in his work "De temporum ratione," described in detail the celebration, which became an integral part of the Anglo-Saxon calendar. Its English name was "Giuli" (Yule). It's worth noting that even after the Roman conquest of Britain, the Julian calendar never became the primary calendar on the islands.

The inhabitants of Foggy Albion continued to use their own calendar and local month names for a long time. For example, December, translated from the ancient British language, was called "before Yule," and January, accordingly, "after Yule." This fact makes clear the importance of the winter solstice.

The peoples of Scandinavia and the British Isles held a spooky belief that the Wild Hunt would sweep across the sky during Yule. This ominous myth is likely familiar to many from the books of Andrzej Sapkowski or video games. According to Norse legends, on this night, Odin himself led a ghostly band of horsemen wandering between worlds in search of the souls of the dead. It was believed that anyone who happened to cross their path would never return to normal life—their sad fate was sealed.

Yule itself was celebrated on a grand scale—for a full 12 days! Each day was a distinct sacred date with its own unique customs and rituals. Some of these have become so deeply ingrained that they have become an integral part of modern Christmas and New Year celebrations. Many of us are unaware that we practice, year after year, traditions that originated long before Christianity became the dominant religion in Europe.

As is well known, the British and Americans hang mistletoe branches and wreaths in their homes for Christmas. They are decorated and placed in prominent places as one of the main symbols of winter celebrations. It is also customary to kiss under this decoration. This tradition has its roots in Yule, as in pre-Christian times, mistletoe was considered a reliable talisman against all evil spirits.

The origins of this belief lie in the myth of Balder, the Norse god of spring, who died tragically from a mistletoe arrow that struck him in the heart. According to legend, his mother, Frigg, wishing to purify the plant from its bad reputation, imbued the mistletoe with a new meaning. She transformed it into a symbol of love and reconciliation. Since then, mistletoe branches have become a symbol not of hostility, but of tenderness, and this is why the custom of exchanging kisses under them arose. Kissing under mistletoe is a more recent tradition, but is linked to the symbolism of love and protection.

Bunches of mistletoe and wreaths of it are hung on the front door. This is believed to be a powerful barrier against evil spirits, preventing them from entering the home. However, in recent years, the tradition of decorating homes with mistletoe has become less popular in the United States. Americans increasingly prefer decorating with simple fir branches.

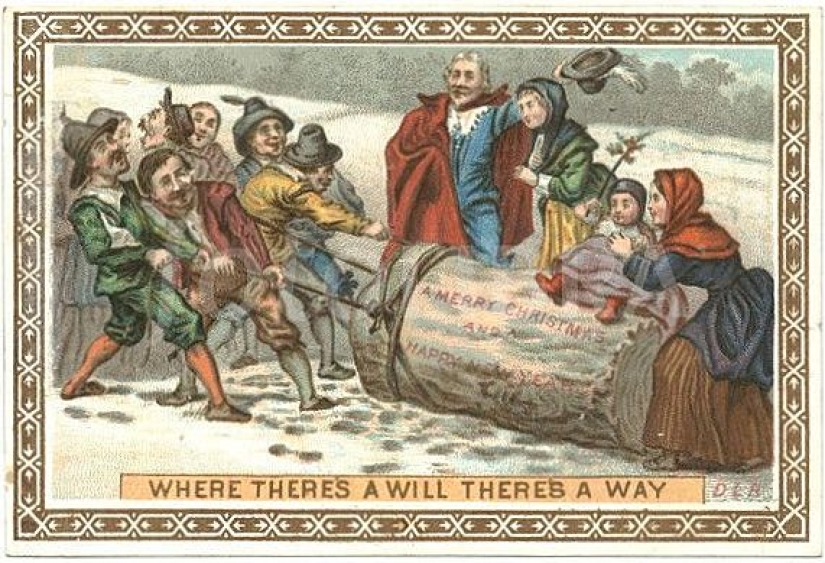

Another curious "plant" tradition is the Yule log. Vikings and Britons prepared a massive oak log in advance, which they ceremoniously burned in the hearth to celebrate the holiday. Once the wood had burned down, the embers and ashes were not to be thrown away for the entire 12 days of Yule. They were supposed to smolder in the hearth, retaining the heat.

After the festival, the ashes were carefully ground into powder and scattered across the fields. This was believed to ensure a bountiful harvest and protect the cattle in the pastures from evil spirits and disease. The burning Yule log symbolized the victory of light over darkness and the long-awaited increase in daylight. This beautiful ritual has become rare today, observed only in certain regions of England and France.

Among the Vikings, any major holiday was accompanied by sacrifices. In Scandinavia and Britain, the most common sacrifice was a boar. The animal was specially prepared and became the centerpiece of a rich holiday table. Incidentally, the tradition of oath-taking was closely associated with the sacrificial boar. If a person wished to swear a solemn oath, they would make their vow by placing their hand on the boar's head.

With the advent of Christianity, any sacrifices naturally came to be frowned upon. The Yule boar ritual faded into oblivion, but its culinary echoes remain. Many cultures traditionally feature roast pork on the Christmas and New Year's tables. The British even call it Yule ham.

The Vikings also had their own unique form of caroling. Noisy groups of young men would go from house to house, singing songs. For this, they received money and tasty treats. This joyful custom was called Wassailing, from the word wassail, which can be translated as "toast" or "congratulations." Singers were always invited to walk through a field or garden. Many believed this guaranteed a bountiful harvest in the coming year.

These days, the constant hero of the winter holidays is Father Frost or Saint Nicholas. Viking mythology, however, didn't feature such kindly figures, but instead featured others, far less sympathetic. The ancient Scandinavians didn't motivate children with gifts from a kind old man; instead, they frightened them with torture and death. After all, the terrifying Yule Goat from Thor's chariot might come for naughty rascals.

The goat strictly checked whether children obeyed their parents. He also carefully examined the adults' clothing. Those who didn't have new clothes or at least a pair of mittens by Yule could easily be taken away by the demonic beast. A lack of new clothes meant that the person had been idle all year and hadn't managed to acquire new things even for the big holiday. Incidentally, the name of the Finnish "Santa Claus," Joulupukki, literally translates as "Yule Goat."

The terrifying Yule Cat (Jólakötturinn) served as the horned guardian of Iceland. Throughout the year, he lived deep in the mountains with the giantess and ogre Grýla. Only during Yule did the enormous black cat descend upon the people. Like Thor's goat, he sought out those who hadn't acquired new clothes for the holiday. The cat mercilessly devoured both children and adults who didn't have a single new woolen garment.

Yule was also a day off for the Vikings. During this period, everyday activities were strictly prohibited, but cooking, feasting, and merrymaking were permitted. Surprisingly, this rule was observed even during harsh military campaigns. Ancient chronicles say that King Harald Fairhair did not attack his enemies for three whole days. It so happened that his longships landed on the shores of Scotland precisely on Yule.

Vikings loved to celebrate, and most importantly, they knew how to do it. The Yule feast lasted as long as there was alcohol and food left. Running out of alcohol suddenly was considered the most unpleasant thing that could happen during a festive feast. Therefore, they prepared for the multi-day feast with the utmost care.

It is known that King Haakon the Good even issued a special decree on this matter. Every man was obliged to prepare grain, brew beer, and bring it to the festival by the end of the year. The king punished anyone who violated the law severely. If, for some reason, a man was unable to brew beer, he could contribute money, meat, or other valuable products.

Of course, Yule has long since lost its mystical significance. But its echoes still live on in our New Year's customs—from lights and decorations to "good luck" rituals. We repeat them automatically, without even considering that they once represented fearsome gods, fear, and the hope of surviving the darkest night of the year. What do you think: should we return to the original meaning of ancient traditions, or should they remain simply the pretty habits of a modern holiday?

Recent articles

It's high time to admit that this whole hipster idea has gone too far. The concept has become so popular that even restaurants have ...

There is a perception that people only use 10% of their brain potential. But the heroes of our review, apparently, found a way to ...

New Year's is a time to surprise and delight loved ones not only with gifts but also with a unique presentation of the holiday ...