"Bread and water are our food": what and how they ate in Russian villages at the end of the XIX century

Categories: Food and Drinks | History

By Pictolic https://pictolic.com/article/bread-and-water-are-our-food-what-and-how-they-ate-in-russian-villages-at-the-end-of-the-xix-century.htmlToday we can go to the supermarket or to the market and choose any products according to our taste and desire. The situation was quite different in peasant families of the XIX century — there the menu was determined by the peculiarities of subsistence farming. In other words, in Russian villages they ate what they had grown themselves, and the food was simple and required a minimum of cooking time.

In the Russian villages of the century before last, housewives did not have time to pamper the household with pickles, so the food was quite simple and rough. Women were forced to be conservative in the choice of products and technologies for their preparation, and only on holidays a certain semblance of diversity appeared on the table.

It should be especially noted the absence of any culinary experiments in the kitchen - the people then were unpretentious in food and the slightest delights were perceived as pampering. The saying "Cabbage soup and porridge are our food" accurately reflected the daily diet of the villagers.

In the Oryol province, the daily food in both poor and rich families was considered "brew", that is, soup or soup. On fast days, this dish was seasoned with pork fat or internal pork fat - "zatoloka", and on lean days, hemp oil was used for this.

In the Petrovsky post, the most popular among the Oryol peasants was a prison made of bread, butter and water - "mura". Festive dishes differed from everyday ones only in that they were better seasoned, for example, meat was added to the "brew", and porridge was cooked not on water, but on milk.

Fried potatoes with meat were considered a special delicacy in peasant homes of the second half of the XIX century. On big church holidays, they sometimes indulged themselves with jelly - jelly boiled from bones and giblets. At the same time, it is worth noting that meat was not a permanent component of the peasant diet.

The Russian economist Nikolai Brzhevsky noted that peasant food almost never satisfied the needs of the body both qualitatively and quantitatively. In other words, malnutrition was common in the villages of the Russian Empire.

Wheat bread was also a rarity on the table. In the economic work "Statistical sketch of the economic situation of the peasants of the Oryol and Tula provinces" (1902) by M. Kashkarov, it was noted that wheat flour was practically not found in rural areas, and products from it in the form of rolls and rolls were usually brought as gifts from the city or from the fair.

When asked about white bread in rural families, Kashkarov most often received one answer: "White bread is for a white body." It is known that at the end of the XIX century in the Tambov province, the ratio of consumed types of bread looked like this: rye flour - 81.2%, wheat flour - 2.3%, cereals - 16.3%.

If we talk about cereals, millet was the most popular in the same Tambov province. Kulish was cooked from it, which was seasoned with pork fat. Vegetable oil was added to lean cabbage soup, and milk or sour cream was added to fast soup. Cabbage and potatoes were considered the main vegetable crops.

In the Russian villages of that time, it was rare to find carrots, beets and other root crops common today. As for cucumbers, they began to grow in Tambov villages already under Soviet rule. Tomatoes appeared last of all — in the 30s of the XX century. But legumes were popular among the peasants: peas, beans and lentils.

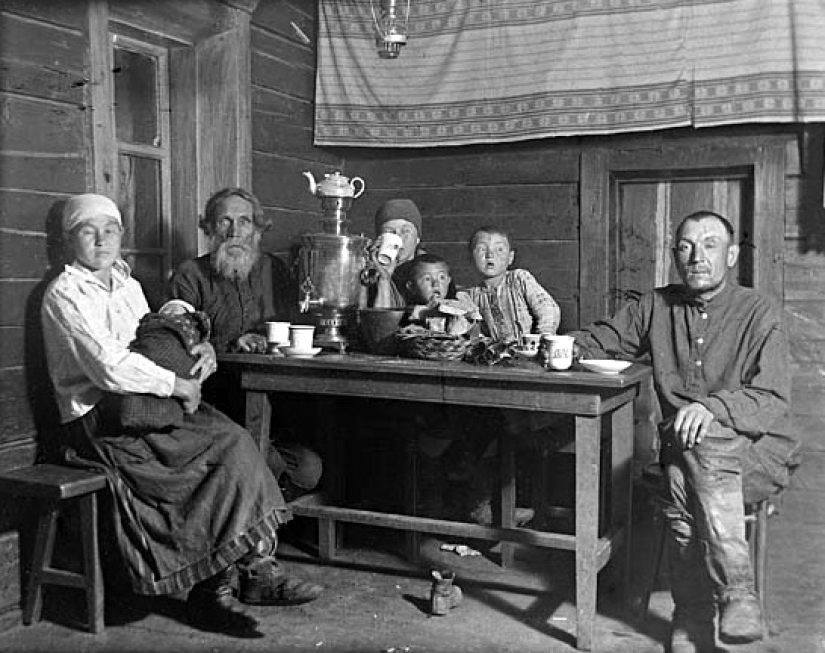

The most popular drink among the peasants was plain water, and kvass was prepared in the summer heat. In the chernozem zone of Russia in the second half of the XIX century, it was not customary to drink tea and this drink was used mainly as medicine, brewed with a cold in an oven in a clay pot.

The diet in peasant families was simple. In the morning, everyone was fortified with what remained from the evening: water and bread, baked potatoes, and other leftovers. Breakfast was at 9-10 a.m. and usually included a brew and potatoes.

Between 12 and 2 o'clock in the afternoon, everyone sat down to lunch and often the same brew was served to the table as for breakfast. Lunch was followed by an afternoon snack, in which, most often, they ate just bread with salt. Dinner in the villages was no later than 9 p.m., and in winter, when it got dark early, it could be much earlier.

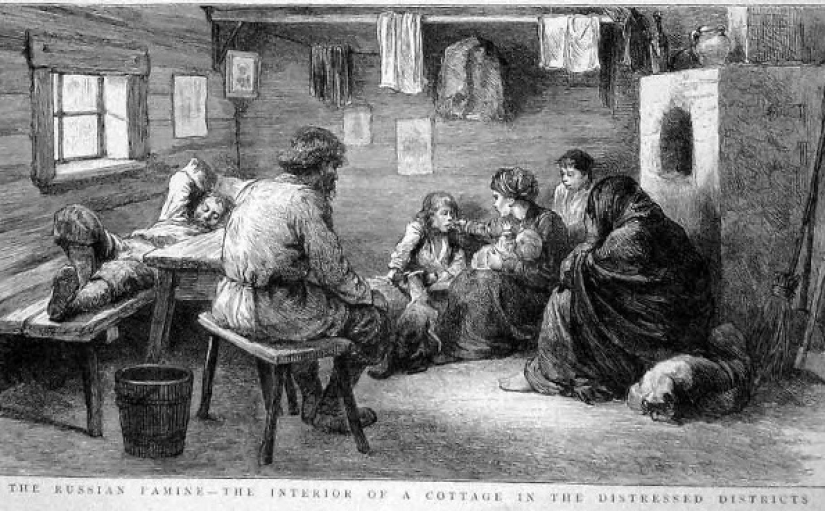

Since the food supplies in the village families were extremely limited, each crop failure was followed by famine. During such periods, the consumption of food by all family members was minimized. In order to survive, the peasants had to slaughter cattle, eat seed material, sell or exchange inventory for food.

In times of famine, in the villages of the Russian Empire, bread was made from buckwheat, barley or rye flour with chaff (garbage obtained by threshing household plants). In 1892, the Russian writer and public figure K. Arsenyev visited the famine-stricken villages of the Morshansky district of the Tambov province and described what he saw in the Bulletin of Europe:

Famine could come in any year, which caused a certain survival tradition to appear in peasant families. This excerpt from the economic report of that time will best tell you about the peculiarities of nutrition in extreme conditions:

Despite the fact that these lines were written during the famine of 1919-1921, little has changed since the days of the Russian Empire and peasant families survived the same as 50 or even 100 years ago. If there were potatoes, they were cooked and seasoned with grated beetroot, quinoa or toasted rye grains.

Bread in times of famine was baked exclusively with impurities, as which potato or beet tops, quinoa, chaff or even the most ordinary grass were used. But even when everything was relatively safe and hunger did not pursue the Russian peasants, it was impossible to call their nutrition full-fledged even with a stretch.

In the European part of Russia in the first years of the XX century, one adult eater who worked hard and hard had only 4,500 Kcal per day and 84.7% of them were of plant origin. Bread accounted for 62.9% and only 15.3% of calories related to animal proteins. Sugar per person per month accounted for less than a pound (435 grams), and vegetable oil even less — only half a pound.

A study conducted at the turn of the century by the Ethnographic Society showed that meat consumption in the European part of Russia was about 20 pounds per year per person in an ordinary peasant family and 1.5 pounds in a wealthy one. Back in 1921-1927, the food of Tambov peasants was 90-95% vegetable, and meat was consumed 10-20 pounds per year per adult.

In the villages, a relatively well-fed period lasted from Pokrov to Yuletide, followed by a half-starved spring-summer period of time. It should be particularly mentioned that the nature of nutrition was seriously influenced by the church calendar. As for poor and well-to-do families, the difference in their diet was expressed not in quality, but in quantity - the rich simply ate more often and more.

Recent articles

It's high time to admit that this whole hipster idea has gone too far. The concept has become so popular that even restaurants have ...

There is a perception that people only use 10% of their brain potential. But the heroes of our review, apparently, found a way to ...

New Year's is a time to surprise and delight loved ones not only with gifts but also with a unique presentation of the holiday ...