Carpathian mythology: what the mountaineers living in the center of Europe believed in

Categories: Culture | Nations | World

By Pictolic https://pictolic.com/article/carpathian-mythology-what-the-mountaineers-living-in-the-center-of-europe-believed-in.htmlThe Carpathians are a large mountain system located on the territory of Western Ukraine, Hungary, Romania, Slovakia and Poland. The Ukrainian Carpathians are the region most familiar to us, inhabited by ethnonational groups of Ukrainians, Magyars, Rusyns and Romanians. The mixture of nations, cultures and religions served as fertile ground for the appearance of a very original mythology here, which is best studied according to Hutsul legends and fairy tales.

Hutsuls are one of the largest ethnic groups of the Ukrainian Carpathians. Their land, which they call the Hutsul region, is relatively small, but incredibly beautiful and at the same time harsh. Only here, among the fast rivers, thundering waterfalls and the slopes of the mountains overgrown with centuries-old forests, can the creatures that we will tell you about live.

Many centuries ago, the Hutsuls adopted Christianity and cherished their faith during the most terrible adversities. Despite this, the Carpathian mountaineers have preserved the authentic beliefs of paganism, which they easily get along with extreme piety. Many customs have been preserved in Hutsul villages since pre-Christian times and some of them cause surprise among guests.

These inhabitants of the Carpathians are attentive to natural phenomena — fire, water, wind, snow. There is a belief that if a child is given bread over a fire, he will grow up to be a criminal, and if you spit into the flame, a burn will appear on the tongue over time. But the Hutsuls have a special relationship with the world of the dead.

Funeral traditions in Hutsul villages were very complicated and, at first glance, illogical. Whole festivities were arranged around the deceased, while they did not hesitate to sing and dance. Seeing off a dead man, in which a priest necessarily participated, was accompanied by many rituals left over from the time of paganism.

The deceased was carried out through the back door feet first, knocking the coffin three times on the threshold. These actions were designed to prevent the dead man from returning home. Hutsuls have always believed that the dead, improperly buried or abandoned without burial, who died not by their own death, who were bad people during their lifetime, turn into different undead and persecute people.

Mavki or navki were considered the most dangerous for the living. These were the souls of stillborn or unbaptized infants, as well as strangled mothers, hanged or drowned children. Mavki look like girls with very pale skin, with loose hair, in long shirts or naked.

In some areas, they were also sure that Mavka could be distinguished from an ordinary girl by the absence of her back. They had a large rotting wound in the back, through which the ribs and insides were visible. Therefore, when she met a lonely traveler in the forest, the spirit girl avoided turning her back to him so as not to give herself away.

Mavki acted both alone and in groups — they lured the enchanted person into the thicket, and then drowned in the river, strangled or tickled until he died. It was possible to resist the magic of these evil spirits only by having holy water with you. And sometimes it was possible to buy off Mavka — an evil spirit could ask a traveler for a comb. If the undead received this simple accessory, it disappeared without a trace. Therefore, when going on a journey through the forest, Hutsul tried to take a wooden comb with him.

The Hutsuls also have devils familiar to the whole of Europe in mythology. Residents of the Eastern Carpathians have created a complex hierarchy for this evil, in which demons are divided by seniority, level of danger and other signs. At the head of the devil's brotherhood is "aridnik", who can also be called "trouble", "Herod", "Satan", "triuda".

Smaller devils obey him — "shcheznyk", "didko", "demons". The unclean of this level were feared as scoundrels and pests capable of breaking utensils, quarreling fellow villagers, causing livestock or human disease. Hutsuls also believed that the devil could be tamed and brought up from him a domestic assistant who performed the functions of a brownie — got rid of pests, calmed children, looked after cattle at night.

It was impossible to educate such an employee yourself, so in order to get it, the mountaineers went to molfar, a local magician and a bearer of ancient mystical knowledge. They became Molfar only by passing on their gift by inheritance. They were engaged in healing, pacification of evil spirits, and also knew how to predict the weather and even change it.

It is believed that the main mystical weapon of the Carpathian magician was the word. Spells, spells and special songs allowed molfar to control the elements, heal hopeless wounds, find missing people. It was these people, who were considered "earthly gods" by the Hutsuls, who could cope with the evil spirits that inhabited the mountain forests.

Molfar's skill was closely intertwined with self—sacrifice - by expelling an evil spirit or a disease from a person's body, he took evil upon himself. To purify himself and gain strength, the Carpathian magician once a year went far into the mountains to caves known only to a select few, where he spent several days without food and drink, communicating with the spirits of nature.

Another advocate from the dark forces of the Hutsuls was considered a chugaister — a Carpathian goblin. He is a very tall, sometimes as tall as a fir tree, bearded old man, overgrown with long gray hair and beard, replacing his clothes. Some legends claim that he has hooves on his feet and horns on his head.

Despite the intimidating appearance, the chugaister is a kind spirit. Some Hutsul legends say that he was once a man, but for some terrible offense he was cursed by God and people and wanders, unable to live as a man or die peacefully.

The main production of chugaister is mavki. He lies in wait for them in the thicket and, having overtaken them, tears them by the legs. By killing and eating evil forest creatures, he protects the people working in the forest. This Carpathian spirit does not feel malice towards a person, but, on the contrary, helps lost travelers, drives lost cattle and protects them from wolves.

Knowing about the chugaister's tall stature, the shepherds left him bread and a bowl of porridge on a beam under the ceiling. If food disappeared at night, it was considered a good sign. The Carpathian goblin does not like foul-mouthed people and people who make noise and whistle in the forest. To educate them, he begins to make noise and catch up with fear, and especially impudent guests can be slightly beaten.

The tall, noisy grandfather is not the only goblin in the Carpathian forest. It was inhabited by quite unkind elders. If a traveler started wandering in the forest, often familiar to him like the back of his hand, then they blamed Fornication for this. This scum looked like a hunched, unpleasant-looking bearded peasant who knows how to turn into various forest animals.

Fornication could spin a person in the thicket so that he lost his last strength and died of hunger and exhaustion. This forest spirit could also lead a traveler to a dangerous cliff, an unreliable ferry or to a den of predators. The wanderer could help himself only if he remembered the dates of the baptism of all relatives and friends, as well as the dishes served on Holy Evening (Epiphany Evening).

The Hutsuls also have their own water, which they call a water man. Outwardly he looks like a Fornication, but his beard is green with algae, and icy water continuously flows down his left side. The waterbird lives in mountain rivers and lakes, through which he travels on horseback on a catfish. This spirit is considered dangerous and unpredictable, as it can drown a swimmer or a wading river just out of mischief.

In addition to the listed evil spirits, Hutsuls believed in many other creatures and spirits inhabiting the thicket, poloniny (alpine meadows), rivers and underground grottoes. Werewolves-vovkulaks, foresters hunting for the souls of people, fox witches tormenting lonely loggers and a whole army of forest spirits and demons of various sizes and degrees of danger, with all their might wished evil to man.

The evil spirits also inhabited the villages and farms of Hutsuls. A hundred years ago, Hutsul families lived in solid log cabins, citizens resembling low defensive towers. Numerous outbuildings crowded around such a house, connected by covered walkways in case of heavy snowfalls and downpours. In such labyrinths there was a place for spirits and devils of different stripes to roam, each of which had its own profile.

In the dark corners of barns and haylofts lived the evil spirits — inconspicuous asexual creatures with a very thin body. They did not bring direct damage, but where they chose a place, there was ruin and poverty. It was possible to catch and expel the villains from the estate by catching them in a saucepan, leaving food there as bait. In the event that a family fell into absolute poverty and did not even have a piece of dry bread to the table, the evil spirits reluctantly went to more prosperous neighbors, also driving them into poverty.

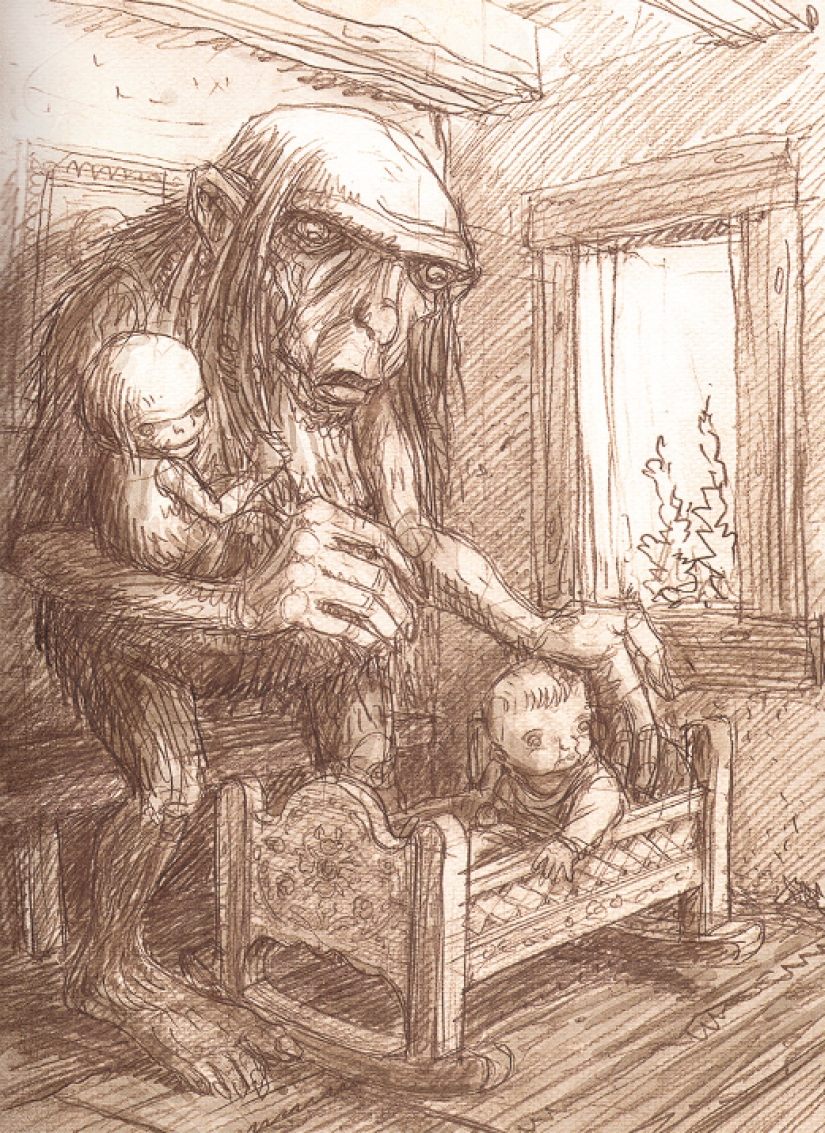

Hutsul women vigilantly took care of babies, as there were many hunters for children's souls in the forest farms. At night, a "wild woman" could get into the house where the unbaptized baby was left unattended. This hostile entity looked like a very thin, untidy woman with a child wrapped in dirty rags in her arms.

The "wild woman" could substitute a human baby for her cub, which was called "odminok". At first it was impossible to distinguish the substitution, but over time the substitution became more and more voracious and loud, while only the head and stomach grew in the "odminka". You could exchange evil spirits for your child by putting the freak in a bag at the intersection. The "wild woman" pitied her screaming offspring and took him away, returning the little man to his parents.

It is worth saying that if there were more than enough pests in the house and around, then good household spirits had to be purchased or begged from Molfar. At the same time, the house-Khovans and the demons re-educated by the magician were extremely capricious and touchy. If the owner of the house offended them in some way, they quickly turned into saboteurs and open pests, which only molfar could cope with again.

PARAGRAPH}

PARAGRAPH}

As we can see, in the life of the Hutsuls, a lot depended on the Molfars and they willingly helped their fellow countrymen, sometimes selflessly. But the white Carpathian magicians also had antagonists — chinitari. These sorcerers knew only harmful and dangerous spells. They were approached with the aim of harming a person or his household, or even to burn an opponent out of the light. Unlike the "earthly gods" who help the suffering, the Chinitari lived on the outskirts, far from villages and passing roads. People shunned sorcerers and considered the places where they could be found to be bad and dangerous.

Today, Hutsuls do not live in citizen towers, although many of them still traditionally graze sheep, make cheese and cut down the forest. In the mountain villages there are neat cottages with air conditioning, and near the gates there are not shaggy Carpathian horses and oxen, but ATVs and SUVs. Despite this, traditions are appreciated here and on holidays they put on bright folk costumes, pick up hatchets and play long trumpets with trembits.

Evil spirits no longer confuse travelers equipped with navigators and no one takes a comb for mavka with them on the road. But in the mountains, they still believe in the powers of molfars and on holidays, no, no, and they will put a bowl of kulesh for a chugaister on the ceiling beam or the top shelf of the kitchen cabinet.

Recent articles

Keishi Kuraibe is a Japanese freelance artist and illustrator who creates his works on the iPad. He loves heavy metal and folklore, ...

Our body is something that is always with us. Nevertheless, if you think about it, this is a unique world of mysteries and unusual ...

With the advent of gadgets in our lives, a lot has changed, including the load on the body. After all, sitting in front of a ...