Rubber Fever, or the Story of a failed economic Miracle

Rubber fever is the closest relative of the gold rush. This term appeared at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, when Brazil and several other South American countries were gripped by a rubber boom. The ever-growing demand for rubber, associated with the birth of the automotive industry and the rapid development of the chemical industry, gave rise to an economic miracle, which, however, quickly faded.

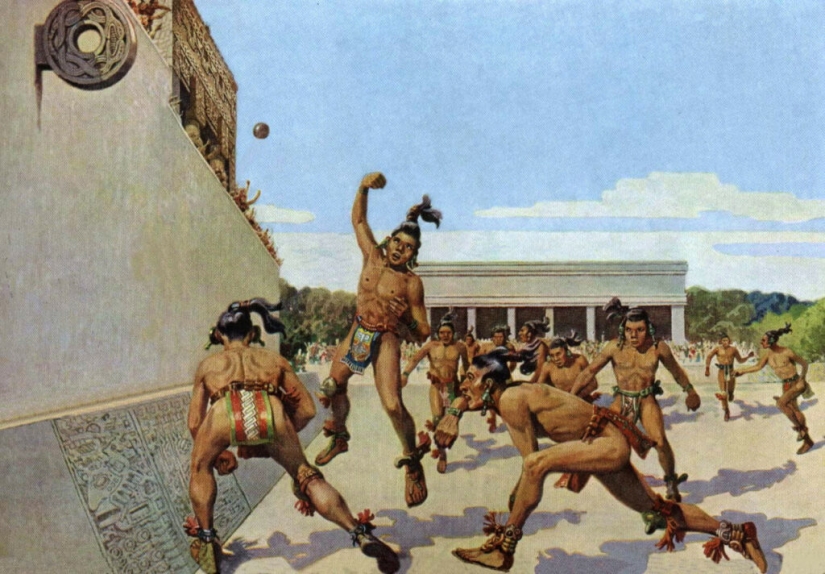

The indigenous population of the Americas has been familiar with rubber since time immemorial. During the excavations in Rubber game balls were found in Mexico, the age of which was 3 thousand years. Members of the second expedition of Christopher Columbus, which took place in 1493-1496, also watched the Indians playing with such balls in Haiti.

For the first time , the technology of rubber extraction and processing was described by the French scientist Charles Marie de la Condamine. He visited South America with an expedition in 1735. The word "kahuchu" translated from the language of the Quechua Indians meant "weeping tree". It very accurately reflected the origin of this substance.

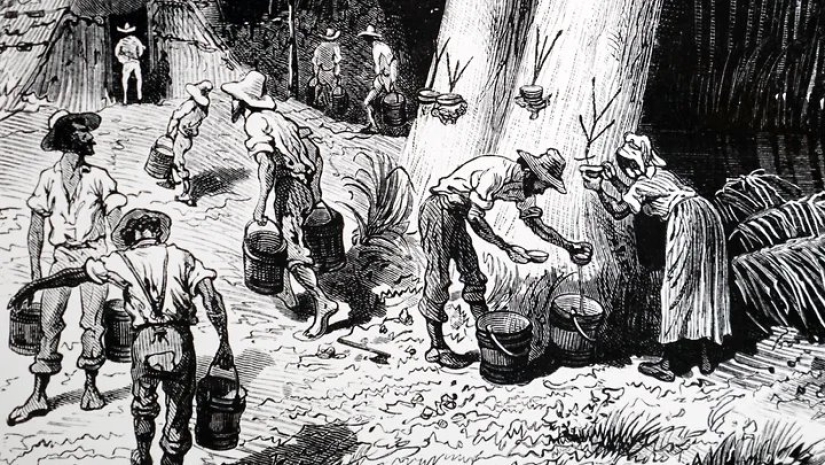

Rubber was made from latex, the milky sap of the Brazilian hevea tree. To get this juice, the Indians made notches on the trunks of the hevei, to which they attached collection containers. The process is very similar to the extraction of birch sap, which is so popular in our latitudes.

Condamine collected rubber samples and sent them with an accompanying note to France. But no one was interested in the scientist's discovery there. The substance could not be used for many decades. It was only in 1770 that the British chemist Joseph Priestley found out that rubber perfectly erases pencil notes. Almost immediately, the rubber eraser was patented by a smart fellow countryman of Priestley named Edward Nairn.

In 1823, another breakthrough was made in the use of rubber. The Scottish chemist Charles Mackintosh managed to impregnate the fabric with it and created the first waterproof raincoats. Then everything went on the rise. After a couple of years, hot water bottles, enemas and shoes began to be produced from rubber. Rubber was regularly brought from Brazil in small batches. For example, in 1827, 31 tons of the substance were delivered to Europe, and in 1830 — 156 tons.

As we can see, rubber did not make a splash in Europe. It should be said right away that this material had a very serious drawback. He was incredibly sensitive to temperature changes. Rubber boots during the heat melted and stuck to the feet, and in the cold turned into stone, and fragile.

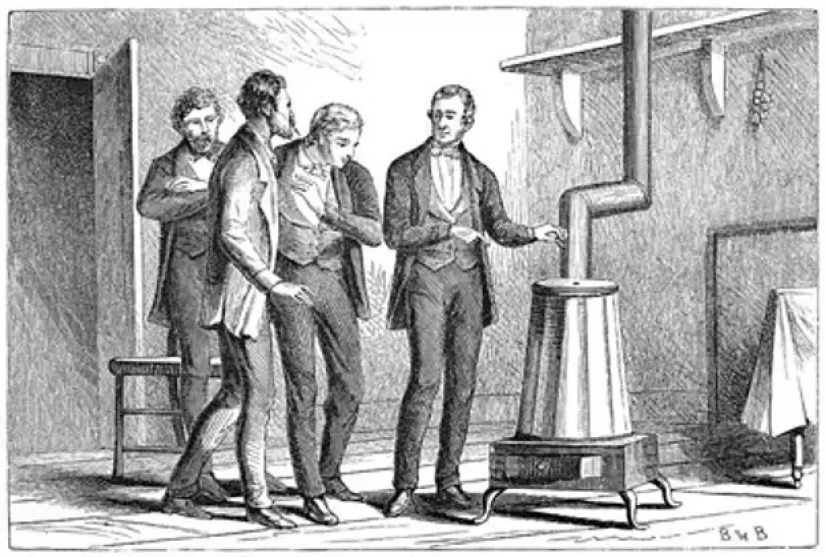

People put up with this until 1839, until they invented the technology of vulcanization. It was invented and patented in 1844 by the American Charles Goodyear. He guessed to mix rubber with sulfur and heat it well. The result was a stable and durable rubber. A variety of products began to be produced from it, ranging from suspenders and children's toys, ending with raincoats and shoes.

Brazil, Peru and Bolivia have started exporting rubber to Europe more and more actively. By 1860, Brazil was shipping 2,673 tons of this raw material to the ports of the Old World. Then it seemed to everyone that this was a real boom! But this was just the beginning of what turned into a rubber fever by the end of the 19th century.

In the last decade of the 19th century, rubber began to find one application after another. Rubber shoes, macs, toys, medical equipment, bicycle and later car tires, insulation for cables — this is not a complete list. The world demanded more and more rubber.

Although rubber was mined in several countries of South America, Brazil became its main supplier. The bulk of the raw materials were extracted in the province of Para, and the centers of the rubber industry were the cities of Belem and Manaus. Once these were rundown towns lost in the Amazon, but rubber has changed everything. The population of the province grew by leaps and bounds.

In 1840, there were barely 100 thousand inhabitants in the province of Para. By 1910, these territories were already inhabited by almost 800 thousand people. Rubber mining, which became the main source of income for these people, was not an easy task. The Amazon jungle was not suitable for the organization of plantations, so expeditions were equipped for rubber.

The main collectors of Hevea juice were Indians. They willingly exchanged valuable raw materials to white people for clothes, jewelry, household utensils, weapons and alcohol. The main supplier of goods for exchange was Portugal. It seems that it would be logical to attract slaves to collect latex. But it was not beneficial to anyone. The areas where rubber was mined were in hard-to-reach places with a terrible climate and slavers simply did not get there.

Traders of African slaves willingly supplied their goods to the plantations of the coast, where coffee was grown. And working in the dark and humid jungle, where danger lurked at every step, became the prerogative of the Indians. The latex collector's profession was called seringero. The collector laid two trails for himself, routes, each in the form of a closed loop. On each path grew 100-200 hevey, from which the juice was collected.

Latex accumulated for a certain time, usually less than a month. Then seringero processed it into rubber and transported it to the buyer responsible for his collection area. The entrepreneur, having collected a significant amount of the product, took it to Manaus or Belem. There, rubber was bought by representatives of large companies, most often foreign.

The rubber business has never been honest. The buyers tried their best to deceive the unfortunate Indians and not pay them. Everything was simplified by the fact that many tribes did not know what money was. The Indians were greedy for various cheap trinkets and gave the fruits of their hard work literally for nothing.

Buyers deceived not only seringero, but also their wholesalers. There were often cases when a small merchant took an advance payment from a large company to buy rubber, and disappeared with it. Later, some latex collectors also learned how to cheat. Seringero added sand to the rubber to make it heavier and more expensive.

But most of the seringeros were in constant debt to the buyers. They willingly gave the Indians advances in goods and money, driving them into dependence. Therefore, collectors often abandoned their boss and ran to another. But even there they quickly became debtors and were forced to flee again. Seringero, who became rich and became a buyer, was a rarity, and there were legends about such people.

One of the largest consumers of rubber was the UK. The purchase of raw materials required more and more funds, and Sir Joseph Hooker, director of the Royal Botanic Gardens in London, suggested growing hevea outside Brazil. In 1873, the seeds of the plant were brought to London to germinate them and then planted in the British colonies.

Out of 2 thousand seeds, only 12 were able to germinate in the botanical garden. Of these, 6 remained in the greenhouse in London, and 6 went to an experimental plantation in Calcutta, India. None of them turned into a tree, and the experiment was declared unsuccessful.

But at the end of the 1870s, their own rubber carriers were discovered in Africa. These were trees and vines that grew in the equatorial part of the Black Continent. African rubber has slowly but surely entered the world market. By 1910, its share in the world market was 57 percent. Africa has its own rubber fever.

And then the persistent Anglo-Saxons managed to organize plantations. They appeared in British Malaya, in Southeast Asia. It turned out that the Brazilian hevea grows perfectly on the Malacca Peninsula and its cultivation there began on a grand scale.

The appearance of plantations has brought down the rubber market. The first raw materials from Asia went on sale in 1900, and in 1912 the Brazilian market collapsed and mass bankruptcies began. It was a real disaster for Brazil. The economic miracle, which seemed to be endless, ended with the bankruptcy of 47 large companies. It is not possible to calculate how many small firms have suffered.

To understand the scale of the disaster, you need to know that in 1915 about 3 thousand houses were empty in Belem. And this is in a city where 10 years before it was impossible to find housing for any money, and people lived in tents and makeshift huts along the streets. By 1930, Brazil had completely lost its reputation as a rubber country. It accounted for only 2 percent of world production.

Recent articles

It's high time to admit that this whole hipster idea has gone too far. The concept has become so popular that even restaurants have ...

There is a perception that people only use 10% of their brain potential. But the heroes of our review, apparently, found a way to ...

New Year's is a time to surprise and delight loved ones not only with gifts but also with a unique presentation of the holiday ...