Life with an outstretched hand: how they begged in tsarist Russia

Categories: History | Nations | Society

By Pictolic https://pictolic.com/article/life-with-an-outstretched-hand-how-they-begged-in-tsarist-russia.htmlFolk wisdom says that you should not renounce prison and the purse. If everything is obvious in the first case, then you can argue about the second part of the saying. Begging before the revolution was a profitable business for many, which did not require investments and allowed them to live better than those who earned money by work.

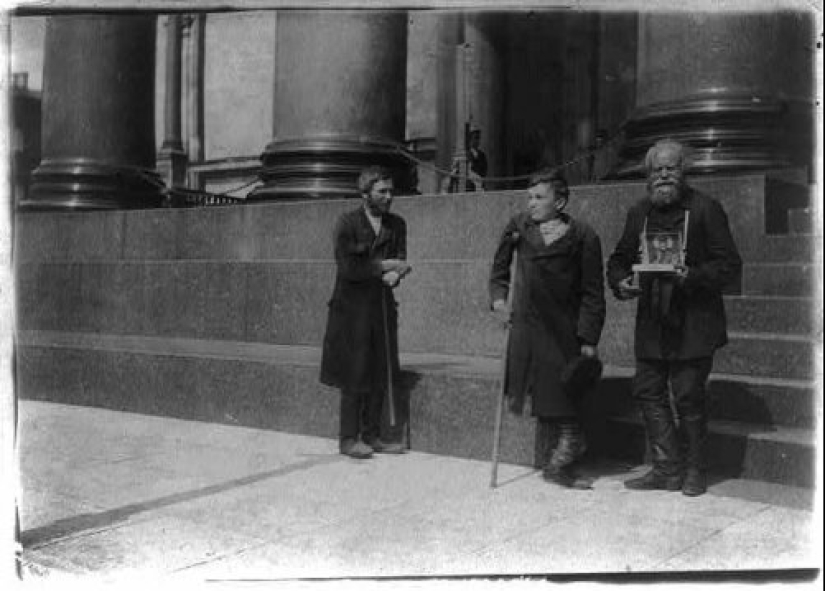

At the end of the XIX century, any believing resident of Moscow or St. Petersburg, before getting to the service in the temple, had to overcome a whole "obstacle course". All the approaches to the cathedrals, starting from the gates and ending with the porch, were densely packed with beggars, who chattered, sobbed, laughed, pulled at their clothes and threw themselves at their feet to get at least some alms from the parishioners.

For an ignorant person, the army of the poor imagined a chaotic mass acting randomly, but an experienced eye immediately noted a serious organization among those asking "For Christ's sake." The mendicant brethren staged whole performances to receive alms. This is how Anatoly Bakhtiarov, a St. Petersburg journalist of the beginning of the XX century, writes about it in his documentary book "Inveterate People: Essays from the lives of dead people":

"... At this time, a rather elderly merchant appeared in the vestibule of the temple. Seeing him, the beggars instantly quieted down and, groaning and sighing, began to sing, begging for alms.

— Give it, for Christ's sake! Do not refuse, benefactor! My husband is dead! Seven children!

— Give it to the blind, the blind!

— Help the poor, unhappy one!

The merchant put a copper in the hand of the "unfortunate widow" and went on. Anton does not yawn: he opened the church doors at the very moment when the merchant was approaching them, for which he also received a copper."

Anton, who participates in the performance, is the husband of a disconsolate widow who is trying to soften the merchant with 7 children. Is it worth adding that if a couple actually have children, then they also work in this field, perhaps even in conjunction with their parents.

Most of the infirm are quite healthy, but they play their chosen roles very convincingly. The same Bakhtiarov describes the moment of the bishop's meeting near the cathedral. One of the beggars, working in the role of a blind man, gives out the phrase:

Performances with beggars were played out in pre-revolutionary Moscow by hundreds, both at temples and just on the streets. Tens of thousands of beggars worked in the capital, having a clear specialization, a dedicated territory and, of course, a paid "roof". In other major cities of the empire, the situation was not much better. Do you remember the dialogue between Panikovsky and Balaganov from the novel "The Golden Calf" by Ilf and Petrov?

This is not a literary fiction and not a joke — the profession of a beggar was actually quite profitable and many ragamuffins fed their families alone and even saved money "for a rainy day."

Where did the tradition of begging come from in Russia? Sociologist Igor Golosenko claims that before the advent of Christianity, the Slavs could not even think that the sick and crippled need to be fed. A natural disaster that spread around the world or disability suggested two solutions: to die of hunger or to go to a more successful fellow countryman as a slave and do all possible work. Those who could not work physically, nursed the children, entertained them with songs and fairy tales, guarded the master's goods.

Christian charity has radically changed the harsh world of pagans — everyone who suffers and needs has now become a "son of God" and it is sinful to refuse him alms. Thanks to this, the streets of cities and villages of Russia were quickly filled with hordes of real cripples and cunning malingerers who howled "Give, for Christ's sake..." under the windows, in shopping malls, at the porches of temples and merchant porches in chorus. Hristaradniki — that's what the merciful donors called these people and tried not to refuse them handouts.

Attempts to curb the beggars were made repeatedly. The reformer Tsar Peter I was the first to solve this problem. He issued a decree forbidding giving alms on the streets. Now anyone who took pity on the poor guy with an outstretched hand was waiting for a hefty fine. The petitioner himself, in case of being caught red-handed, received whips and was sent out of the city. Someone went to his homeland, to a God-forsaken village, and a beggar, caught again, went to explore Siberia.

As an alternative to begging, the tsar ordered the opening of many almshouses, shelters at monasteries and hospices, where the poor were fed, watered and provided with a roof over their heads. Of course, Pyotr Alekseevich's initiative failed and the beggars preferred to take risks than to sit on starvation rations in four walls, waiting for death.

Other Romanovs also took up this issue. For example, Nicholas I in 1834 issued a decree on the creation of a Committee for the analysis and charity of beggars in St. Petersburg. This institution was engaged in sorting tramps and beggars caught by the police into real disabled and seasoned "pros". The first tried to help with treatment and small payments, and the second was again sent to sunny Siberia to cut down the forest and dig ores. This good initiative also failed — the number of beggars on the streets of cities has not decreased.

The number of masqueraders reached its apogee after wars and epidemics, and the abolition of serfdom in 1861 turned the invasion of beggars into a real disaster of imperial scale. A third of the peasants of Russia, who were, in fact, in the position of slaves, found themselves free without money, property and land that fed them from generation to generation. More precisely, the allotment could be obtained from the master by law, but for this it was necessary to redeem it, which almost no one could do.

Tens of thousands of former peasants rushed to the cities in search of a better life. Only a few of them were able to adapt by organizing their own small business or reforging into the proletariat — most joined the already huge army of beggars. Historians still do not agree on the total number of members of the mendicant brotherhood — their number in Russia at the end of the XIX century is estimated from several hundred thousand to two million.

It is known for sure that at the beginning of the XX century, from 1905 to 1910, 14-19 thousand beggars were detained and registered only in Moscow and St. Petersburg annually. This figure makes it clear the scope of the phenomenon. Beggars earned their bread quite easily — a little artistry, a couple of tearful stories and a simple inventory - that's all that was needed to start a career.

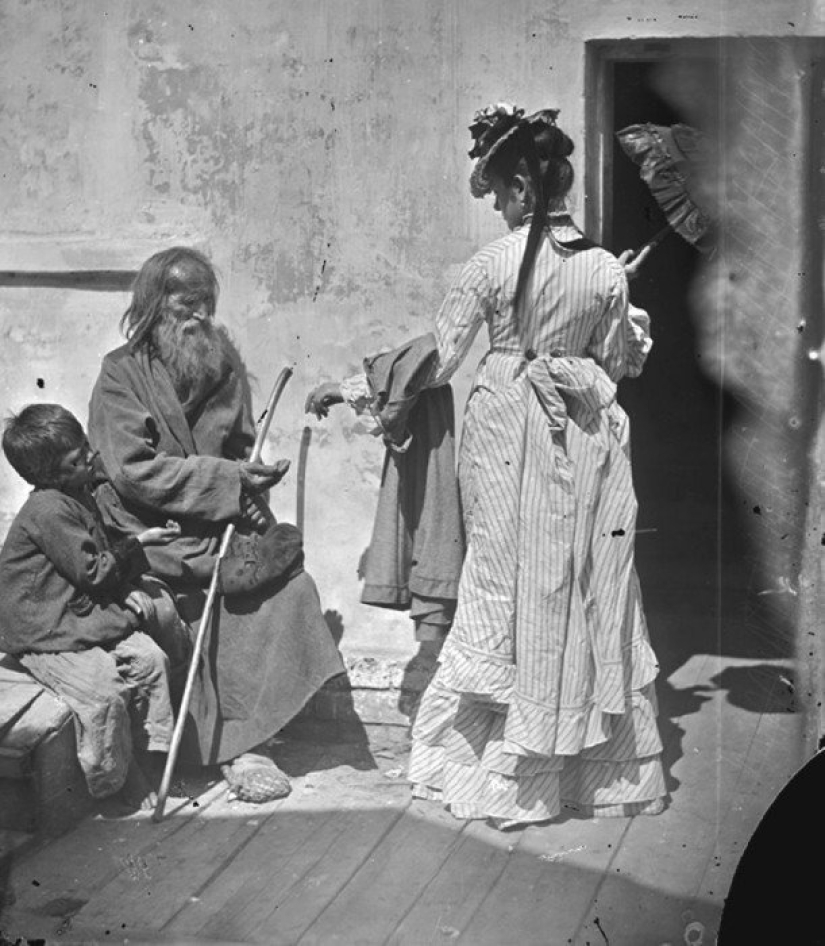

Merchants and intellectuals willingly served beggars, pitying them and sincerely believing in the stories told. It is difficult to say how many sleepless nights writers, poets and philosophers spent thinking about the "fate of the Russian people", inspired by the tales of real and imaginary cripples and homeless.

The mendicant brethren were divided into groups according to their specialization. The most prestigious "profession" was working on the porch. The so-called "mantises" can be called the elite of beggars. In the presence of some talents, money got to these beggars relatively easily and from the disadvantages of the specialty, only high competition can be called.

It was not easy to get into the "mantises" at all. All the beggars who worked at the temples were in artels, where they carefully distributed their places of work. A stranger who entered someone else's territory risked serious injury, as in the fight against competitors, the sick and crippled knew no pity. It was also possible to get on the neck and from their own, in case of violation of the schedule. If one poor begged for alms at matins, then by the evening service he had to hand over the post to his colleague.

Less monetary, but also not too dusty, was the work of "gravediggers" begging in cemeteries. At the appearance of the "crucian carp" (as the deceased was called in the jargon of beggars), the crowd of beggars rushed to the inconsolable relatives and friends shaking their rags, moaning and demonstrating real and "fake" sores and injuries.

There was a clear calculation of psychologists — grieving and confused people always serve willingly and more than in other situations. The profession of the "gravedigger", like the "mantis", was quite monetary. Often, beggars were an order of magnitude richer than the givers.

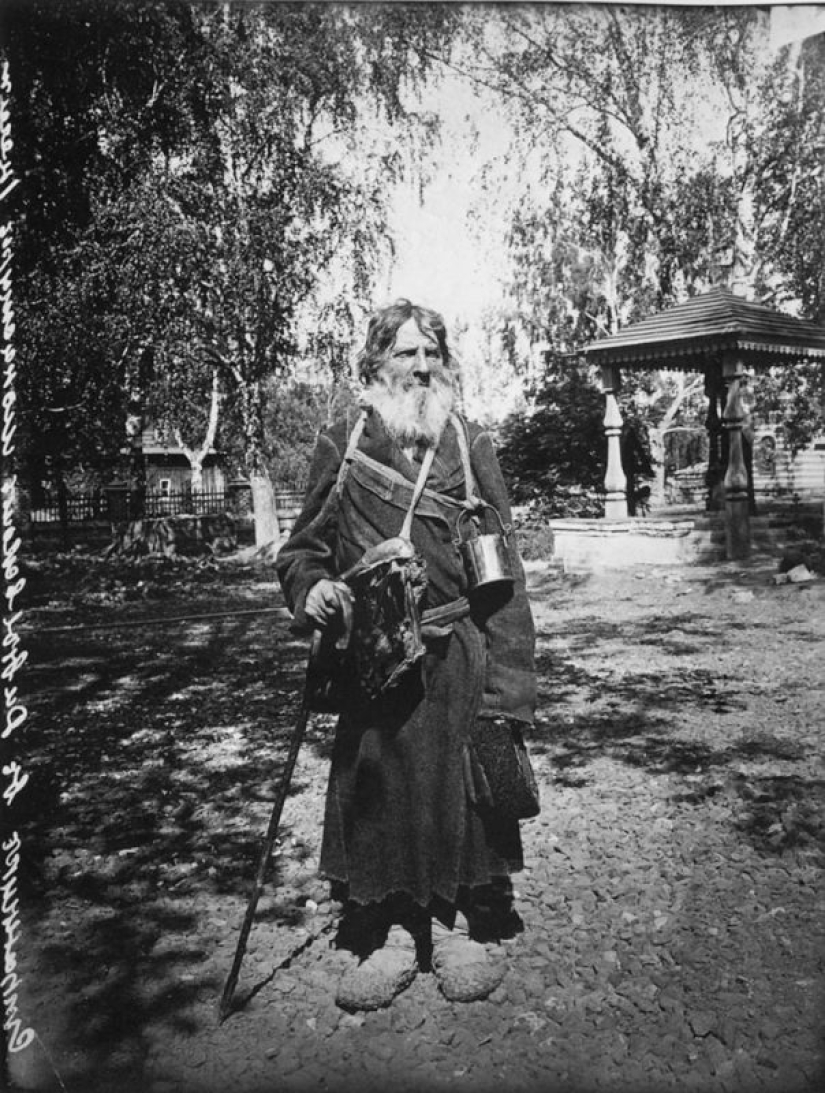

The role of the Jerusalem wanderer enjoyed great success. In this case, even mutilation was not required — a mournful face and black clothes were enough. A pious Orthodox pilgrim who returned from worshiping Holy Places inspired respect and religious awe in the layman, which was used by beggars. Their methods of work were special — they asked modestly and unobtrusively, sometimes even with dignity. In return, the pitcher received a blessing and a few hackneyed tales about distant countries.

Fire victims or "firefighters" are another category of petitioners who worked wherever possible. These people portrayed peasants who had lost their house and belongings as a result of a fire and were collecting for the restoration of a dwelling or the construction of a new one. Fires were commonplace in Russia, which was built of wood, and no one was immune from such a disaster. Therefore, such beggars were willingly served, especially if they worked in groups in the company of dirty, sobbing children and a grief-stricken spouse.

There were always very numerous immigrants who told a simple story that they had left their home in a remote starving province in search of a better life and were forced to wander suffering the most incredible hardships. This way of begging was not the most profitable, since usually the "settlers" worked in groups, dividing the loot among themselves equally or by right of the strong.

Also, a huge number of cripples worked in the Russian Empire. Among them were both real invalids and those who exaggerated their infirmity or even invented it. To simulate deformity or the consequence of injury, a variety of methods were used, from banal crutches, to tying raw meat in the body in order to simulate severe illness. Many "legless" showed miracles of stoicism, sitting on sidewalks or at churches with their limbs tucked up for long hours. When exposed, such cripples were often beaten and even arrested with forwarding to the already familiar lands beyond the Ural Ridge.

Beggars-writers have always been considered a special, "white bone" in Russia. These people often had a good education, had a trustworthy appearance and dressed neatly. They worked according to a special scenario, not stooping to begging on the streets. Such a type would go into a merchant's shop and with dignity ask the clerk to call the owner or turn to a lonely, handsome lady.

At the same time, the pressure was not on religious feelings, but on human compassion. The writer told a short but plausible story about what prompted him, a noble man, to stoop so low and stretch out his hand. It was important to choose the right narrative here — the ladies willingly served the victims of unrequited love and intra-family intrigues, and the trading people ruined and lost at cards to entrepreneurs.

It should be noted that not much has changed since then and these specializations, somewhat modified, still exist. In addition, nowadays there are many new ways to beg from gullible citizens, and professional beggars have become more cynical and quirky.

Recent articles

We invite you to take a break from your evening affairs for a moment and take a look at the naughty photo set of funny girls in the ...

Relatively recently, the world began to learn about gender diversity. Started talking about a lot of things that have never been ...

Frank De Mulder is rightfully considered a living classic of erotic photography. His work has graced the pages and covers of iconic ...