Dance over the Abyss: The Story of Edith Eger, the Little Ballerina from Auschwitz

Categories: Children | History

By Pictolic https://pictolic.com/article/dance-over-the-abyss-the-story-of-edith-eger-the-little-ballerina-from-auschwitz.htmlThere are many terrible pages in the history of the 20th century, but the Holocaust is one of the most painful. Millions of lives were broken, families destroyed, childhoods erased. But in the darkness there were people who, having gone through unimaginable pain, not only survived, but were able to become a light for others. One of them is Edith Eva Eger. Her story is not only about surviving in a concentration camp, but also about the strength of spirit, forgiveness and inner freedom that no executioner can take away.

Edith Elefant was born on September 29, 1927, in the Slovak city of Košice. She was born into a large family of tailor Lajos Elefant, who was famous for his craftsmanship. He always had plenty of orders, and the family did not need anything. However, Edith and her sisters Magda and Klara grew up under the strict control of their parents. Despite their material well-being, childhood was not easy for the girls due to the constant demands of their parents.

Lajos and his wife Ilona raised their children strictly, maintaining iron discipline in the house. Magda, Klara and Edith learned to play several musical instruments from an early age, and also sang in a choir. When it became clear that Edith had no special musical talent, her parents did not give up their attempts to develop her abilities. At the age of five, the girl was immediately sent to a ballet school.

In her teenage years, Edith became interested in gymnastics. At first, she thought it was useful for improving her dancing skills, but soon the girl truly loved this sport. Gymnastics quickly took the main place in her life, pushing ballet into the background. In 1938, the situation changed dramatically: Hungary annexed Kosice, and hard times began for the Jewish family. Yellow stars on their clothes, strict restrictions and constant fear became an integral part of their daily life.

The young athlete Edith showed excellent results, and she was even considered as a candidate for the Olympic team. But the dream did not come true - all because of her Jewish origin. However, those Olympics were never held. It was the beginning of the 1940s, when World War II was already raging in Europe, and the life of Jews was becoming more and more dangerous every day. In 1941, 14-year-old Edith met her first love - a teenager named Eric. They spent a lot of time together. Eric, who was fond of photography, often took pictures of Edith doing gymnastics exercises.

The relatively calm life of the Elefant family lasted until the summer of 1943. In August, the Nazis took Edith's father to a labor camp. He was released six months later, but in March 1944, the entire family was sent to forced labor. They were sent to the Jakab brick factory. From there, the Jews had only one way out — to the Auschwitz concentration camp.

Of the entire family, only Klara escaped arrest. When the soldiers came to the tailor's house, she was giving a concert in Budapest. She was saved by her music teacher - he did not let the girl go home and until the end of the war he passed her off as his Magyar daughter. Fortunately, Klara had the facial features typical of non-Jews. But Ilona, Lajos, Magda and Edith, having found themselves in the brick factory, did not even suspect what awaited them ahead. They were told that the family would be sent to an ordinary internment camp, where they would wait for the end of the war.

The family spent a month at the factory. More than 20,000 Jews awaited their fate with them. Later, Edith and her family were loaded into a freight car and taken somewhere. Many years later, Edith Eger would write in her book that she was ready to give up a lot just to get back to that car. After all, that was where their family was together for the last time.

The Jews were brought to the Auschwitz concentration camp and immediately on the platform they were divided into two groups. One included those aged 14 to 40, and the other included everyone else. Lajos and Ilona were over 40 and were separated from their daughters. The older group of prisoners was taken away, supposedly to take a shower. In reality, they were all sent to the gas chambers.

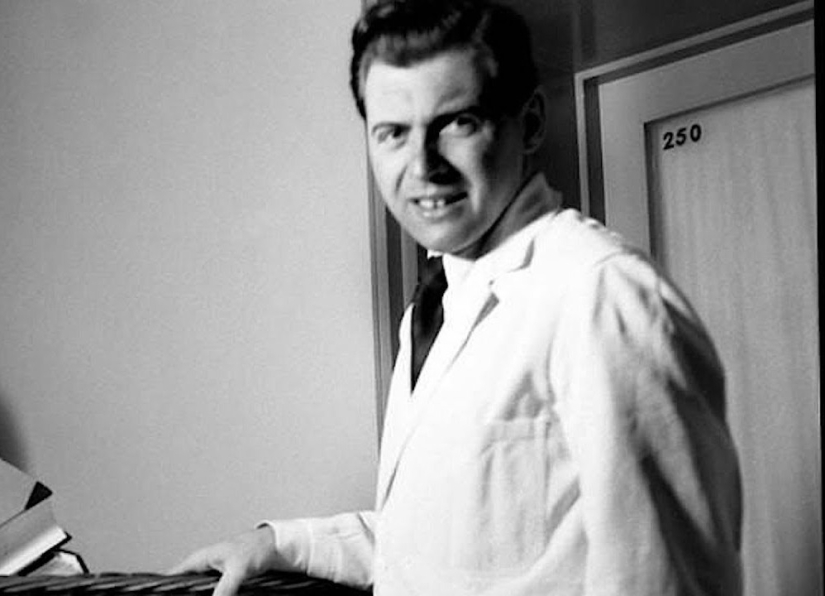

After that, terrible days began, full of cold, hunger and exhausting labor. Soon, only a shadow in a gray camp uniform remained of the former cheerful ballerina and athlete Edith. However, when Dr. Mengele himself came to the barracks and began looking for dancers, someone pushed the teenager out of line. "Dr. Death" was in a good mood and wanted to be danced for.

An orchestra of prisoner musicians, at the doctor's command, began to play Strauss's waltz "On the Beautiful Blue Danube." Edith was lucky - she knew this dance. After that, Tchaikovsky began to play, Edith danced with her eyes closed, imagining that she was on a theater stage. Mengele liked the performance - he praised the prisoner and gave her a loaf of bread. Edith immediately shared it with her sister and several other neighbors in the barracks.

Edith's skills soon saved her sister's life. The prisoners in their barracks were lined up to have a number tattooed on their arm. The emaciated dancer was not in line; her guards sent her to a separate group. At the time, she couldn't understand what it meant. Typically, such separations ended with one group being sent to the gas chamber.

Edith decided to take a risky step and distracted the guards by doing a few cartwheels. While the Nazis watched her tricks, Magda quietly ran over to her sister. The girls were lucky: they were simply sent back to the barracks. The Germans decided to separate the most puny prisoners so as not to waste the tattoo artist's time and paint on them. They figured that these "unaccounted for" prisoners would soon die of exhaustion anyway and there was no point in wasting gas on them either.

In the camp, Edith realized that even in hell, a person can choose whether to dwell on suffering or find meaning in order to live on. It was this position that helped her survive until the end of the war. In November 1944, Soviet troops began to approach Auschwitz. The Nazis began to destroy traces of their crimes and prepared the camp for evacuation. On Himmler's orders, they blew up the gas chambers and crematoria.

When the gradual evacuation of prisoners began, Edith and Magda were considered strong enough to survive the journey. Along with other prisoners, the sisters were taken from Poland to Germany. There, a multi-day "death march" began. The prisoners were driven along the country's roads from factory to factory. For a time, they worked, making military products, and then they were sent on their way.

In March 1945, the greatly thinned out column of Auschwitz prisoners arrived in Austria, at the Mauthausen concentration camp. There were no factories or plants there – the prisoners worked in a granite quarry and stone quarries. From there, the survivors were transferred to the tiny Gunskirchen camp, designed for only 200 prisoners. The emaciated Edith was carried there by her barracks neighbors in their arms. During the “death march,” Edith had injured her spine. Her condition was critical: pneumonia, typhus, and a back injury nearly took her life.

The conditions of the prisoners in Gunskirchen were appalling. It was not a place for work or housing, but a place for people to die. Edith and Magda soon found themselves outside in the rain, in a pile of bodies, some dead, some dying. They were lucky: the camp was liberated by American troops. Doctors at the military hospital were barely able to save the girls.

During her treatment, Edith met a partisan, Bela Eger, who would later become her husband. After the war, Edith and Magda returned to their native Košice, where their sister Klara was already waiting for them. There, Edith learned that her fiancé Erik had died in Auschwitz just one day before the camp’s liberation. The trauma she had suffered during the war and the guilt of surviving haunted her for a long time.

Soon Bela Eger came to Edith, and they got married. The newlyweds settled in Eger's estate in Czechoslovakia. Bela was a wealthy man, and the couple soon had a daughter. But their family's happiness was short-lived. In 1948, the communists came to power in Czechoslovakia.

Bela was arrested and his property was nationalized. Edith managed to secure her husband's release, but they had to leave the country. The Eger family settled in the United States with Magda, and Klara moved to Australia. In America, Edith, her husband, and daughter settled in El Paso, Texas. There they had two more children.

Family life was not ideal. Inspired by Viktor Frankl's book "Man's Search for Meaning", Edith decided to study psychology. She dreamed of getting a degree in psychology, but her husband was categorically against it. Because of this conflict, they divorced in 1969. However, they soon realized that they could not live without each other, and in 1971 they remarried. Edith still completed her studies and received a diploma. In 1978, she defended her doctoral dissertation. After that, she began working as a psychologist, helping military personnel and women who had experienced violence.

In 1999, Edith Eger came to Auschwitz. She wrote about this difficult but necessary journey:

Edith Jaeger collected her thoughts and experiences in the book “The Choice”. It was published in 2017 and quickly became a bestseller. In it, the author shares not only her memories of Auschwitz, but also important lessons that helped her and her patients. The main idea of the book is that freedom begins when a person accepts what happened and decides how to live on. In 2020, her second book, “The Gift”, was published.

Today, Dr. Edith Eger is a world-renowned psychologist whose lectures attract thousands of listeners. Her story is not just a tale of survival. It is an example of how trauma can be turned into strength. Edith has proven that even after hell, it is possible to build a happy life, help others, and leave a mark on the world.

Edith will soon be 100 years old. She has seven great-grandchildren, whom she calls “the best revenge on Hitler.” This amazing woman continues to work in California, inspiring people through books, speeches, and personal consultations. Her motto is: “The prison is in our heads, and the key is in our hands.” These words remind us that the choice is always ours.

The story of Edith Eger is not only a story about the past, but also a source of inspiration for the present. Her life demonstrates that a person can be stronger than fear, pain and injustice. Do you think it is possible to forgive what seems unforgivable? And how can we learn to choose the light even in the darkest moments of life?

Recent articles

It's high time to admit that this whole hipster idea has gone too far. The concept has become so popular that even restaurants have ...

There is a perception that people only use 10% of their brain potential. But the heroes of our review, apparently, found a way to ...

New Year's is a time to surprise and delight loved ones not only with gifts but also with a unique presentation of the holiday ...