Why did foreign ambassadors get drunk in Russia

Categories: History

By Pictolic https://pictolic.com/article/why-did-foreign-ambassadors-get-drunk-in-russia.htmlIt is said that Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavovich of Kiev, who baptized Russia, responded to the offer to convert to Islam: "We can't have fun in Russia, we can't live without it...". No one really knows if this was the case. But it is well known that Russian people were not averse to drinking always and expected the same from the guests. Even the most official, that is, ambassadors.

Europeans who arrived in Moscow with important business, fell into despair from the amount of alcohol they were supplied with. The source of alcohol was inexhaustible. Even on the day of departure, the diplomat was generously presented with wines and intoxicating honey, "on the way."

The Italian Raphael Barberini, who in 1564 brought Ivan IV a letter from the English queen, wrote about the meeting with the Moscow tsar as follows:

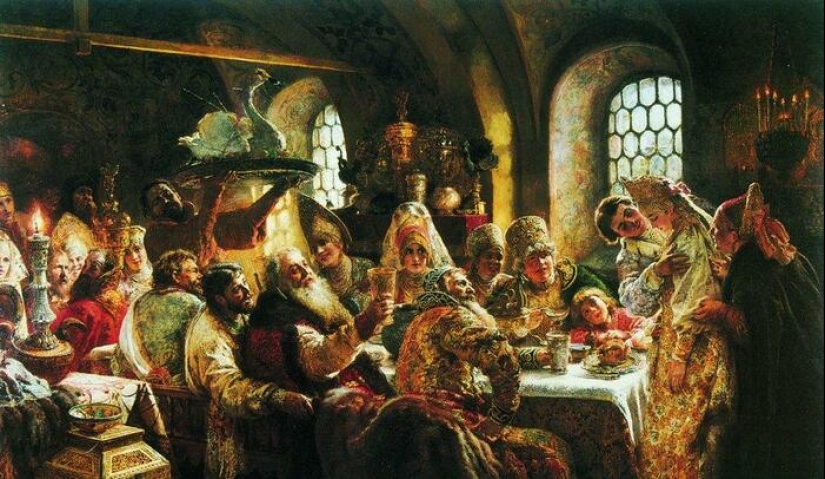

Barberini was not alone with his alcohol observations. Many foreigners admitted that they sat down at the table with the tsar and the boyars, with an unpleasant premonition. They knew that they would have to drink a lot and for a long time, which made it extremely difficult to observe diplomatic etiquette, or even just the rules of decency.

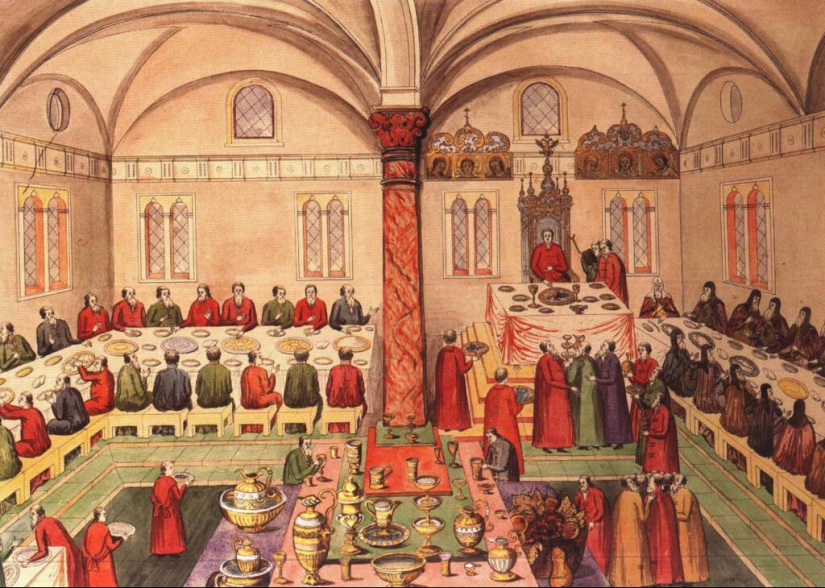

In the 15th and 16th centuries, sovereigns personally regaled overseas guests with alcohol, enjoying their intoxicating spontaneity. But later there were too many ambassadors. In addition, the attitude towards diplomats has changed a little. There were disagreements with some countries and it was unpleasant for the tsars to seat their ambassadors at their table. In this regard, the royal feast with booze became a privilege. It extended to the most expensive and important guests.

The secretary of the Danish embassy Andre Rode, who visited Moscow with the envoy Hans Oldeland in 1659, described the beginning of the meal in the company of the tsar:

The secretary mentioned that at first the ambassador was given a glass of vodka to drink "for appetite." After that, everyone present was poured a large glass of hock. In the 17th century, an ordinary cup contained at least 120 grams. Therefore, the envoy was already rather cool to the hock.

Foreigners were terribly afraid to get drunk and disgrace themselves in front of the Russians. But at the same time, among the royal dignitaries, it was considered an honorable thing to get drunk at the royal table. It was believed that this perfectly demonstrates respect for the sovereign and gives an assessment of his hospitality.

The Austrian diplomat Augustin von Meyerberg wrote in the same 17th century that it was supposed to drink until exhaustion and no one left the royal feast until it was taken away. The Austrian did not like receptions and was burdened by such a custom. With emotion, von Meyerberg recalls a visit to Afanasy Ordin-Nashchokin, one of the most prominent diplomats of Muscovy. He was a fan of the European way of life and saved the envoy from having to drink before falling under the table.

But it was just a nice exception. Neither other Russian diplomats nor other nobles allowed envoys of other powers to leave the feast on their own two feet. At the same time, drunkenness was encouraged not only at official and informal meetings, but also in their free time.

Bread wine, which was what vodka used to be called, was an indispensable part of the provisions laid down for the ambassador. The royal court regularly supplied embassies with this alcoholic beverage, which was quite expensive in the 16th and 17th centuries. The production of vodka was a state monopoly, so there was always an abundance of it in government warehouses.

There are records that take into account the alcohol given to John Meyrick, the British ambassador in Moscow. The diplomat was at the court of Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich in the 17th century. Every day he was supposed to have four glasses of vodka (about half a liter), a cup (1.1 liters) of grape wine, three cups of honey, one and a half cups of mead and a bucket of beer.

Meyrick's companions were not deprived of Russian hospitality either. Every English nobleman could count on four cups of bread wine (not as strong as the ambassador's), a cup of honey, three-quarters of a bucket of plain mead and half a bucket of beer every day. Even the servants from the embassy suite were given two glasses of vodka and half a bucket of beer.

One might think that the huge doses of alcohol that ambassadors rely on were designed to show cordiality and generosity. Yes, it was so, but besides that, other insidious goals were pursued. It was easier to find out secrets from a drunken guest and it was easier to impose your will on him.

Therefore, the ambassadors and their retinue were watered always and everywhere. Even in the embassy courtyard, diplomats could not hide from drinking. Back in the 15th century, the custom appeared to visit the ambassador and give him a drink at his place of residence. Sigismund Herberstein, having visited Moscow in the 16th century, described it like this:

It's not that the diplomat condemned other people's orders, but even now there is a sense of utter hopelessness from his notes. Herberstein wrote that Russian nobles used unsportsmanlike ways to force them to drink. When they noticed that the guest was starting to mess around and skip, or even refuse to drink, Byzantine cunning was used. The guest was offered to drink to the sovereign, the tsarina, tsarevichs and others. Of course, it was impossible to refuse. Agree, a very modern method.

But all this was childish babble compared to how the ambassadors were drunk under Peter the Great. Neither before nor after did diplomats drink as much as they did under the reformer sovereign. The Holstein nobleman Friedrich Wilhelm Berchholz, who often drank in the company of the tsar, described his fear of drinking. He also shared some tricks that would surely have angered Peter.

Duke Karl-Friedrich of Holstein-Gottorp, whose interests were represented at the Russian court by Berchholz, pitied his subject. He gave him good advice:

The duke himself, who had visited the Russian tsar more than once, could not use his method. He, as a distinguished guest, was next to Pyotr Alekseevich. He personally made sure that the noble guests got drunk to the point of fainting. One day Peter caught the Duke diluting wine and was very angry.

It is worth saying that feasts with Peter the Great sometimes led to tragic consequences. Duke Frederick William of Courland, for whom the Russian tsar married his niece Anna Ioannovna, died two days after the wedding. The reason for this was a rash desire to compete in the art of drinking with the sovereign. So young Anna was widowed immediately after the wedding.

Peter the Great was the last Russian tsar who adhered to the principles of "alcoholic diplomacy". After that, the gallant period of crazy empresses came and the custom of watering ambassadors to complete amazement sank into oblivion.

Recent articles

It's high time to admit that this whole hipster idea has gone too far. The concept has become so popular that even restaurants have ...

There is a perception that people only use 10% of their brain potential. But the heroes of our review, apparently, found a way to ...

New Year's is a time to surprise and delight loved ones not only with gifts but also with a unique presentation of the holiday ...