How the Jesuit Order Changed the World

Categories: History | Society | World

By Pictolic https://pictolic.com/article/how-the-jesuit-order-changed-the-world.htmlOn August 15, 1534, the Society of Jesus was born in the heart of Paris, which would later become known as the Order of the Jesuits. But how exactly did this religious organization influence the course of world history? Immerse yourself in the depths of time and find out how one unification of people could change the face of entire nations and continents.

By the first half of the 16th century, in many countries of Western Europe, the Catholic Church had lost its former influence. Seeking to control everything and under the leadership of the Pope, Catholicism faced the challenges of reformation. As a result, millions of Christians have ceased to be Catholics. The authority of the traditional church in countries such as Germany, England, Switzerland and Scotland was undermined. However, Catholicism still had the power to counteract.

This stage in history is called the Counter-Reformation. Measures were tightened against heretics and dissidents, the Inquisition was reorganized, a list of banned books was created, and the laity were forbidden to read and discuss the Bible. The main vehicle for Catholic reaction at this time was the Society of Jesus, the military arm of the active church. We know this society as the Order of the Jesuits.

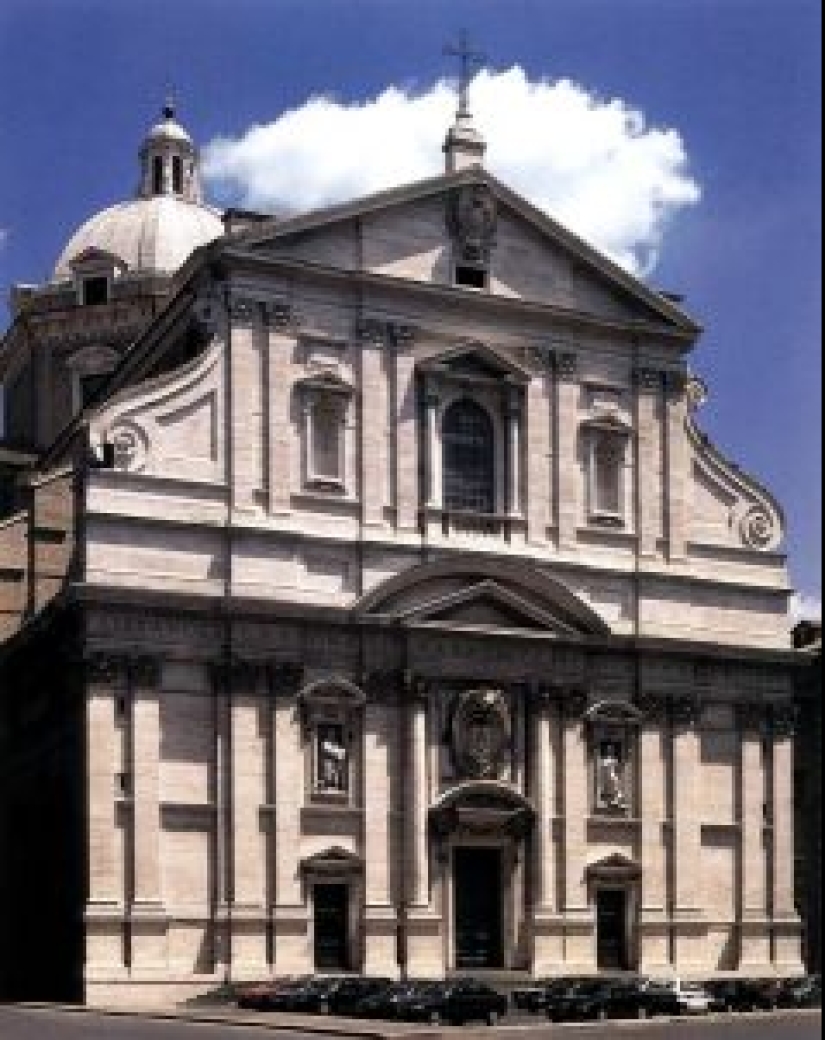

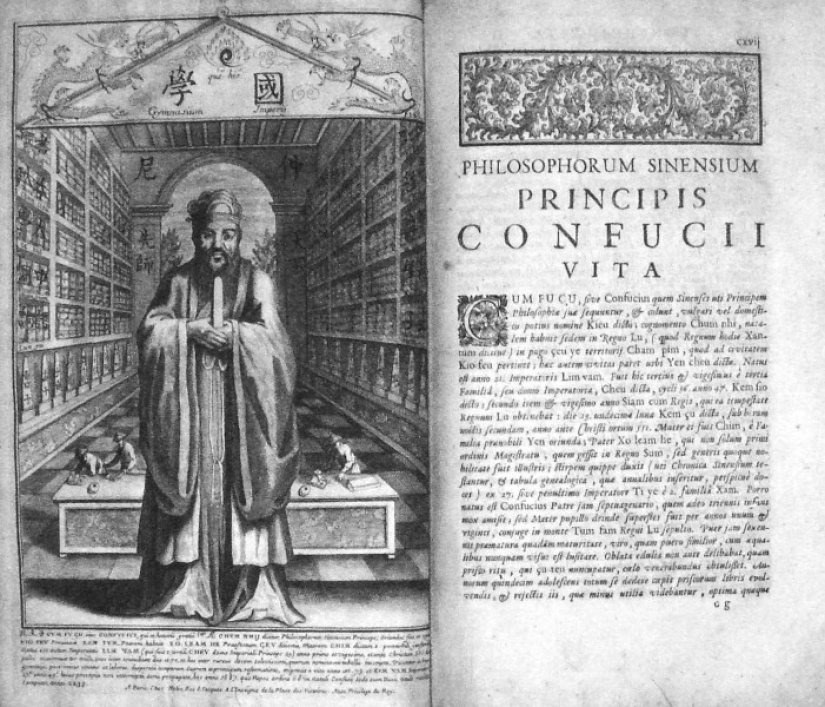

The Jesuit Order was founded in 1534 in Paris thanks to the efforts of the Spanish aristocrat Ignatius Loyola, and in 1540 received a blessing from Pope Paul III. Since the Protestant Reformation, members of this order have often been referred to as "the infantry of the Pope", in part because of the military background of its founder, Ignatius Loyola. The motto of the Jesuits was the phrase "Ad majorem Dei gloriam", which in Latin means "For the greater glory of God."

According to Wikipedia, the founder of the Society of Jesus, Ignatius de Loyola, was born in 1491 in Basque territory in Spain. While serving under the viceroy of Navarre, he was wounded during the blockade of Pamplona in 1521 and was transferred to Loyola Castle. There he spent many months recovering from the battle and found a spiritual awakening by reading the book The Life of Christ. After recovering, the aristocrat decided to go to Jerusalem as a poor pilgrim. But en route he stopped at Manresa, where historians say he had a profound spiritual insight that provided the basis for his Spiritual Exercises, a text that Jesuits have been taught for centuries.

In 1523, Ignatius went to Jerusalem to study the traces of the life of Jesus, "whom he wished to get to know better, whom he strove to imitate and follow." Upon his return, Layola continued his education in Barcelona and later in Alcala. But due to a conflict with the Inquisition and a short prison term, he was forced to leave Alcala and move to Salamanca and later to Paris, where he entered the Sorbonne. Over time, a group of like-minded people formed around him, among whom were Pierre Favre from Savoy, Francis Xavier from Navarre and the Portuguese Simon Rodriguez. Under the guidance of Ignatius, they all underwent spiritual exercises. When they got together, they discussed spiritual and religious matters, especially concerning the current state of the Catholic Church.

For them, there were two priority directions in their religion: to know Jesus Christ deeper and follow his path, and also to return to true evangelical poverty. They devised a plan to go to Jerusalem immediately after completing their studies. And they decided that if they could not do this, then they would go to Rome and put themselves at the disposal of the pope for "any mission among the faithful or unfaithful."

On August 15, 1524, in a chapel in Montmartre, seven friends solemnly confirm their spiritual plan by making vows during the liturgy. About eleven years later, by the end of 1536, the number of this group had grown to ten people. They are heading from Paris to Venice with the goal of going on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. But due to hostilities with the Ottoman Empire, travel becomes impossible. So, the group changes its course and goes to Rome, where in November 1537 they offer their services to the Church. However, facing the possibility of division into different missions, friends come to a decision about the need to preserve their unity. They are convinced that by the will of God they were gathered from different parts of the world and different life paths, and this obliges them to maintain strong bonds with each other, remaining united in a single “body”.

Then the attitude towards the monastic orders was far from the best, because many blamed them for the crisis that engulfed the Church. Pope Paul III was skeptical about the idea of creating a new order, fearing that the Jesuits might follow the path of the reformers. Therefore, he approved the organization of the order with the proviso that its members would not exceed 60. However, this condition was canceled a year later. Ignatius Loyola was elected rector of the order.

During the last fifteen years of his life, until his departure, Loyola actively directed the Society of Jesus and developed its basic statutes. After his death, the first Congregation finalized and finalized these rules, choosing also his successor.

The Council of Trent was indeed a critical moment in the history of the Roman Catholic Church. This council was convened in response to the Protestant Reformation that began with the actions of Martin Luther in 1517, and its purpose was to define and clarify the doctrinal teachings of the Church, as well as to reform many of its practices.

The main doctrinal decisions of the council were directed against the teachings of the Protestant Reformation. The council confirmed the doctrine of the seven sacraments, the doctrine of transsubstance in the Eucharist, the authority of the pope and bishops, and the need for clergy. The council also decided which books should be considered canonical in the Bible, rejecting the Protestant canon.

In addition, the council was engaged in the reform of the internal practices of the Church, including the education of priests, liturgy and discipline. These reforms were intended to eliminate many of the abuses that had caused the Protestant Reformation.

Returning to the Jesuits, their role in the Counter-Reformation (the response of the Catholic Church to the Protestant Reformation) was critical. Their education, discipline, and dedication were important tools for the Church in its attempt to win back the many believers lost in the Reformation. Thus, the Jesuits played a key role not only in missionary activities in the new lands, but also in the struggle for faith in Europe itself.

The Jesuits did have a huge impact on education in many parts of Europe and beyond. Their educational system was focused on the all-round development of the individual and sought to provide a thorough education that combined the humanities, sciences and religious disciplines.

Building on this educational legacy, the Jesuits were influential in shaping the cultural and intellectual landscape in the places where they worked. They sought to create educated, moral and spiritually developed people who could serve their societies and the Church. But, as you rightly pointed out, their methods and influence also caused controversy and conflict, especially among those who saw them as competition or a threat to their interests.

The successes, as well as the methods and ideology of the Society during the first century of its existence, aroused rivalry, envy and intrigue against the Jesuits. In many cases, the struggle was so fierce that the order almost ceased to exist in an era overwhelmed by the movement of the most controversial ideas, such as Jansenism (the doctrine emphasized the corrupted nature of man due to original sin, the need for Divine grace, as well as predestination), quietism (the doctrine proclaimed complete passivity and calmness, submission to the divine will, indifference to good and evil, renunciation of the world). Nevertheless, the 16th and 17th centuries were the heyday of the power and wealth of the order; he owned rich estates, a mass of manufactories.

Pedagogical activity was put forward as one of the main tasks of the order by its founder. So, in 1616, there were 373 Jesuit colleges (closed educational institutions), and by 1710 their number had increased to 612. In the 18th century, the vast majority of secondary and higher educational institutions in Western Europe were in the hands of the Jesuits. And it is not surprising, because one of the main activities of the order in the field of education was the creation of a network of educational institutions and the education of young people from privileged or wealthy strata in the spirit of devotion to Catholicism.

In the 17th-18th centuries, the Jesuits had a reputation as brilliant educators and teachers, as they accumulated the achievements of pedagogy of their time: a class-lesson teaching system, the use of exercises, the transition from easy to difficult. In education, the emphasis was on the development of ambition, says the Great Russian Encyclopedia. The spirit of competition was maintained: the best and lagging behind were regularly noted, competitions and disputes were held.

1st stage: anyone from the age of 19 could enter and for two years study what he would do in the future

2nd stage: two years of general education subjects

3rd stage: philosophy and natural sciences were studied for three years

Stage 4: Regency Preparation for becoming a teacher of theology

5th level: theology - the candidate prepared himself for the hierarchs of the church

And on the sixth he entered into an initiation that took several months. He was ordained into the brotherhood, that is, he received certain revelations. Note that any candidate studied for 14 or 15 years to become a Jesuit. The required vows for members of the order are: a vow of chastity, a vow of poverty, and a vow of obedience.

From the best students, "magistrates" were formed, whose members bore the honorary titles of patricians and senators (by analogy with Ancient Rome), "directors" (guardians from the senior classes over younger students), as well as "academies" (such as school circles), were chosen " rectors". Students were prepared for active work, so the Jesuits abandoned the rules of the medieval monastic school: they took care of the health, physical development, nutrition and rest of the pupils. An important place was given to secular education. But the main thing was religious education. The development of the personality of the individual was combined with strict regulation of the behavior of students, subordination of personal will to the interests of the church, the introduction of mutual supervision during and after classes, the obligatory denunciations of the misconduct of comrades (did you think that the Soviet government invented this? - ed.).

The Jesuits developed their own system of morality, which they called "adaptive". It gave a wide opportunity to arbitrarily interpret the basic religious and moral requirements, depending on the circumstances, and to perform any act (sometimes criminal) in the name of the "higher goal" - "For the greater glory of the Lord." Such an official value of morality was reflected in the motto attributed to the Jesuits "The end justifies the means."

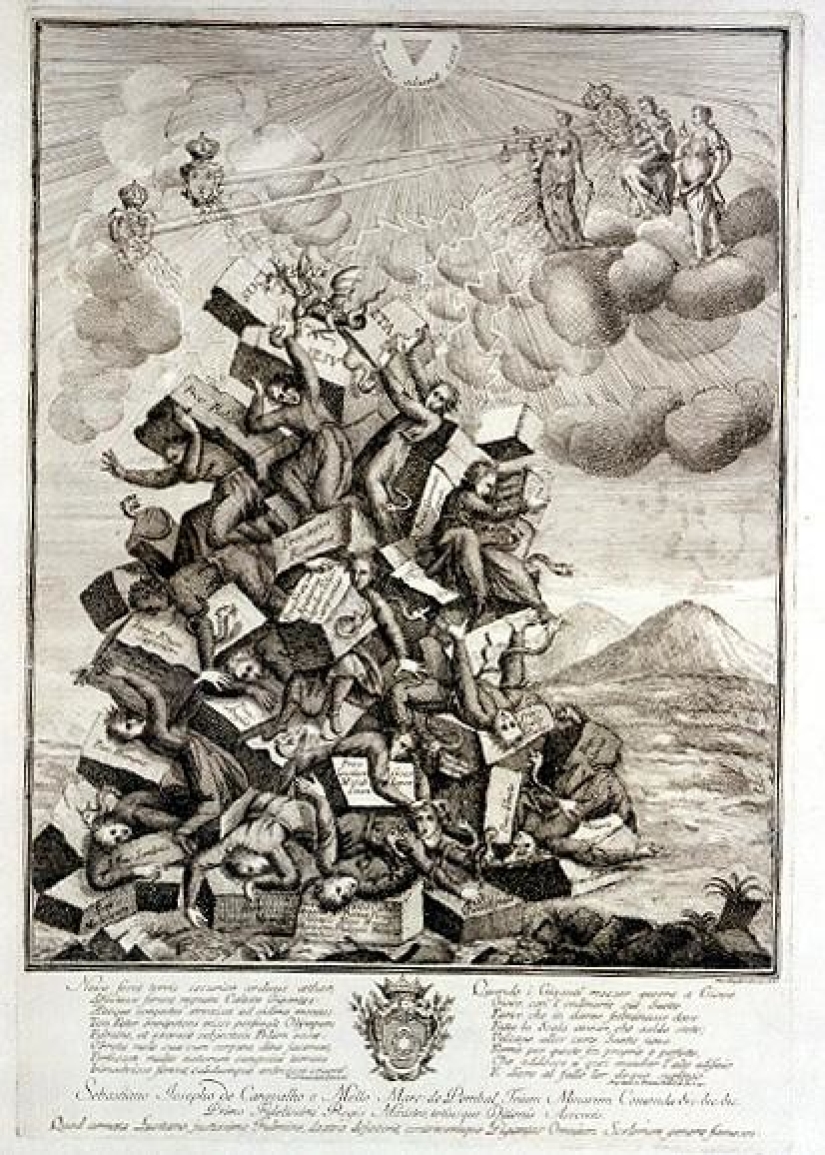

In 1770, the Order included 23,000 members, 669 colleges and 273 missions. However, the monarchs of all European countries were against the existence of a secret and strong organization that acted in the interests of the Catholic Church and was in no way controlled by their power. The pope was forced to dissolve the order. However, already in 1814, Pope Pius VII restored the Jesuit order in all its rights and privileges.

In addition to theology, the Jesuits founded astronomical and seismological stations in Manila and China, and the Roman astronomer Secchi (1818–1878) gained worldwide fame. The contribution of the Jesuits to fiction was extensive and varied: the writings of the English Jesuit Hopkins (1844-1889) deserve special mention. Jesuit periodicals include La Civilt cattolica (Italy, 1850), Etudes (tudes, France, 1856), Stimmen der Zeit (Germany, 1865), Mans (The Month, England, 1864), Rason and Fe (Razon y Fe, Spain, 1901) and America (America, USA, 1909).

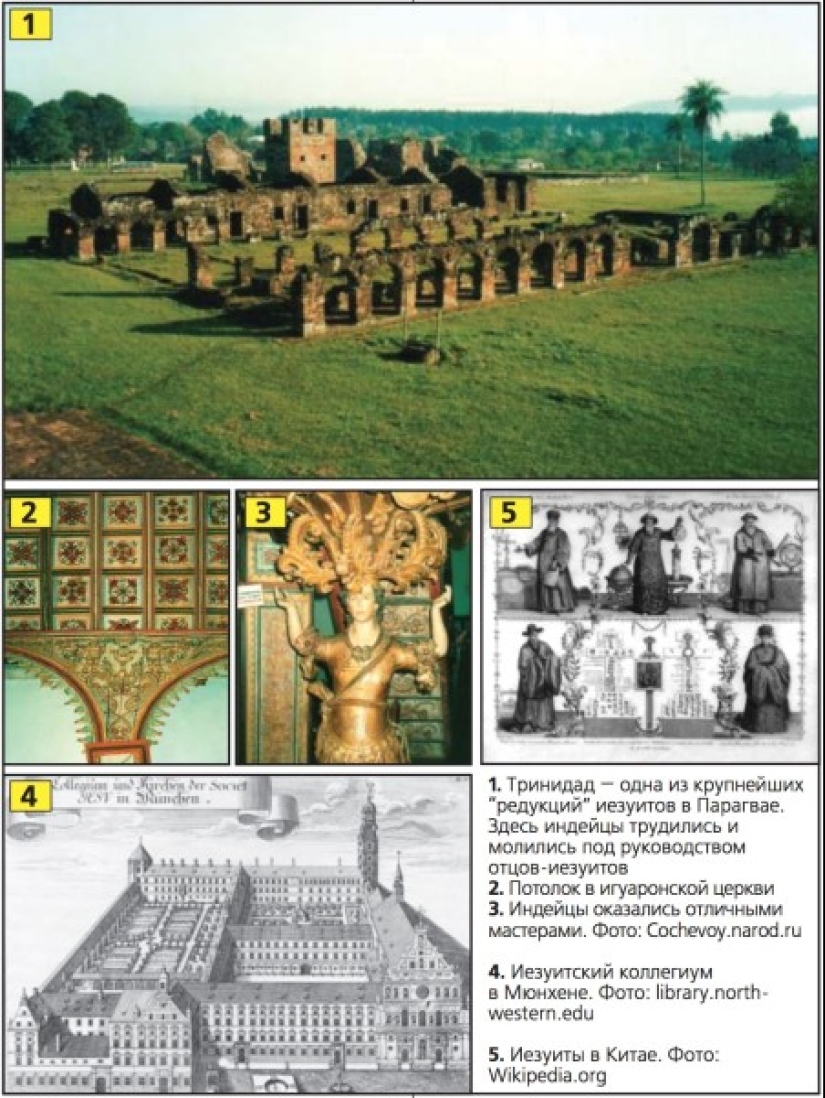

For a long time, the population of Paraguay was made up of Indians of the Guarani tribes. Missionary activity was initiated among them by the Dominican friar Las Casas. As Igor Shafarevich writes in his work “Socialism as a Phenomenon of World History”, the Jesuits, with their characteristic realistic approach, decided to make the adoption of Christianity practically attractive, and for this they tried to protect the converted Indians from their main disaster - the slave hunters, the Paulists from the state of San Paulo, then the center of the slave trade.

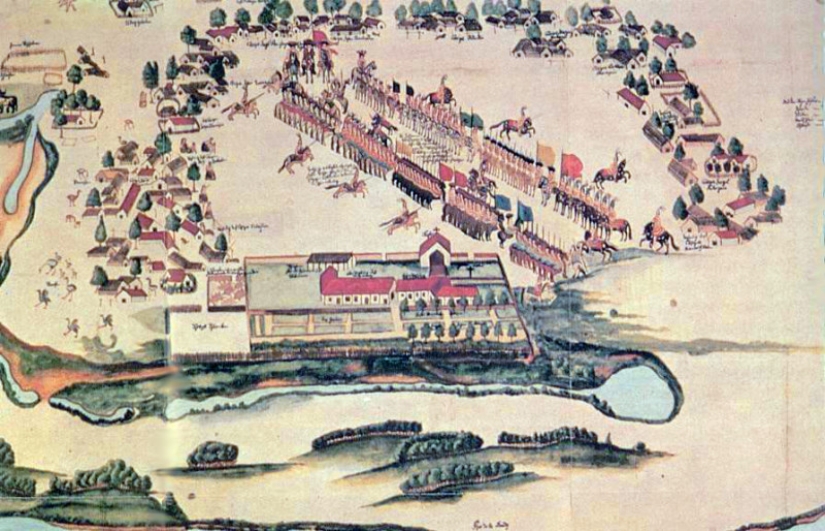

The Jesuits accustomed the Indians to settled life and moved them to large villages called reductions. The first reduction was founded in 1609. At first, apparently, there was a plan to create a great state with access to the Atlantic Ocean, but this was prevented by the Paulist raids. Beginning in 1640, the Jesuits armed the Indians and with fighting moved them to a remote area, bounded on one side by the Andes, and on the other by the rapids of the Parana, La Plata and Uruguay rivers. By that time the whole country was covered with a network of reductions. Already in 1645, the Jesuits Masheta and Cataladino received from the Spanish crown a privilege that freed the possessions of the Society of Jesus from subordination to the Spanish colonial authorities and from paying tithes to the local bishop. The Jesuits soon won the right to equip the Indians with firearms and created a strong army from the Guarani.

The Jesuits steadfastly denied accusations that they had created an independent state in Paraguay. In fact, some accusations were exaggerated - for example, a book about the "Paraguayan emperor" with his portrait, or the coins allegedly issued by him were a fake of the enemies of the Jesuits. But there is no doubt that the area controlled by the Jesuits was so isolated from the outside world that it could well be considered an independent state or dominion of Spain.

The Jesuits were the only Europeans in the area. They obtained from the Spanish government a law according to which no European could enter the territory of the reductions without their permission, and in any case could not stay there for more than three days. The Jesuits did not teach Spanish to the Indians, but developed the Guarani script and taught them to read and write. The Jesuit region had its own army and conducted independent foreign trade.

The population of the state of the Jesuits at the time of its heyday was 150,200 thousand people. The main part of them were Indians, in addition, about 12 thousand Negro slaves and 150-300 Jesuits. The history of this state was cut short in 1767-1768, when the Jesuits were expelled from Paraguay as part of the general anti-Jesuit policy of the Spanish cabinet.

The entire population was concentrated in reductions. Usually two or three thousand Indians lived in the reductions, in the smallest - about five hundred people; the largest mission of St. Xavier numbered thirty thousand inhabitants. Each reduction was headed by two Jesuit priests. As a rule, one of them was much older than the other. There were usually no other Europeans in the reduction. The eldest of the two priests, the "confessor", mainly devoted himself to the cult, the younger was considered his assistant and managed the economic affairs.

All life in reductions was based on the fact that the Indians owned almost nothing: neither the land, nor the houses, nor the raw materials or tools of the artisan were private property, and the Indians themselves did not belong to themselves. All manufactured products were handed over to warehouses, in which Indians trained in writing and counting worked. Part of the food was distributed to the population. The fabrics were divided into equal pieces and distributed by name. Each man received annually a knife and an axe.

Most of the production in reductions was exported. So, with huge herds, a large number of skins were dressed. The missions had tanneries and shoe shops. All their products were exported - the Indians were only allowed to walk barefoot. Foreign trade was carried out very widely. The reductions exported, for example, more local tea than the rest of Paraguay.

Many were amazed by the ability that the Indians showed in the craft. Charlevoix writes that the Guarani “succeeded, as it were, instinctively in any craft they encountered ... For example, it was enough to show them a cross, a candlestick, an amulet, or give them material to make them do the same. One could hardly distinguish their work from the model they had in front of them.”

Trade did not exist either within the reduction or between the reductions. There was no money either. Each Indian held a coin in his hands once in his life - during the marriage, when he handed it as a gift to the bride, so that the coin would be returned to the father immediately after the ceremony.

All reductions were built according to the same plan. In the center was a square square on which the church was located. Around the square there was a prison, workshops, warehouses, an arsenal, a spinning workshop in which widows and delinquent women worked, a hospital, and a guest house. The rest of the reduction territory was divided into equal square quarters.

In contrast to the housing of the Indians, the churches were striking in their luxury. They were built of stone and richly decorated. The church in the mission of St. Xavier accommodated 4000-5000 people, its walls were decorated with shiny plates of mica, the altars - with gold.

At dawn, the Indians were awakened by a bell, according to which they had to get up and go to prayer, which is obligatory for all, and then to work. In the evening, they also went to bed on a signal. At nightfall, detachments made up of the most reliable Indians patrolled the village. It was possible to leave the house only with special permission.

All the Indians dressed in the same cloaks from the matter received in the warehouse. Only officials and officers had different clothes from others, but only when they were performing their public duties. The rest of the time, she (like weapons) was stored in a warehouse. Marriages were made twice a year at a solemn ceremony. The choice of wife or husband was under the control of the pater.

The children started working very early. “As soon as the child reached the age when he could already work, he was brought to the workshops and assigned to the craft,” writes Charlevoix. The Jesuits were very worried that the population of reductions was almost not growing - despite the completely unusually good conditions for the Indians: a guarantee against hunger and medical assistance. To encourage fertility, the Indians were not allowed to wear long hair (the mark of a man) until the birth of a child. With the same purpose, at night, the bells called them to the performance of marital duties.

Meanwhile, the Jesuits themselves did everything to stifle the Indians' initiative and interest in the result of their work. The Regulations of 1689 say: "You can give them something to make them feel satisfied, but care must be taken that they do not develop a feeling of interest." It was only towards the end of their reign that the Jesuits tried (probably for economic reasons) to develop private initiative, for example, by distributing livestock into private ownership. But this did not lead to anything - not a single experiment was successful.

The Jesuits in Paraguay, as elsewhere in the world, have ruined themselves by their successes - they have become too dangerous. In particular, in reductions they created a well-armed army, numbering up to 12 thousand people, which was, apparently, the decisive military force in the area. They intervened in internecine wars, stormed the capital Assuncion more than once, defeated the Portuguese troops, and freed Buenos Aires from the siege of the British. During the turmoil, they defeated the governor of Paraguay, Don José Antequerra. Several thousand Guarani armed with firearms, on foot and on horseback, participated in the battles. This army began to inspire more and more fears to the Spanish government.

The fall of the Jesuits was greatly facilitated by the widespread rumors about the colossal wealth they had accumulated. After the expulsion of the Jesuits, government officials rushed to look for the treasures they had hidden and found that they were not there. Most of the Indians fled from the reductions and returned to their former religion and wandering life.

An interesting assessment that the activities of the Jesuits in Paraguay received from the philosophers of the Enlightenment. For them, the Jesuits were enemy No1, but some of them could not find high enough words to characterize their Paraguayan state: “The spread of Christianity in Paraguay by the forces of the Jesuits alone is in a sense a triumph of mankind.”

In the 60s of the XVI century, the Jesuits established themselves in the Commonwealth. On January 13, 1577, a bull of Pope Gregory XIII was issued on the formation of the Greek College, in which pupils from the East Slavic lands of the Commonwealth, Livonia and Muscovy were to study. In the XVI-XVII centuries, the Jesuits founded a number of educational institutions on the territory of the Commonwealth. And in the 16th century, the Jesuits, who acted in the same place, published about 350 theological-polemical, philosophical, catechistic, preaching works.

In the summer of 1684, an embassy from the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire arrived in Moscow to negotiate Russia's entry into the Holy League, says the Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron. The embassy included the Jesuit Vota, who was supposed to help organize a Jesuit mission in Moscow. In 1684-1689, the Jesuits launched an active activity in Moscow and began to influence the favorite of Princess Sophia, Prince Golitsin. In 1689, after the accession to the throne of Peter I, the Jesuits were expelled from Russia. At the end of the 17th century, they were again allowed to settle in Moscow, where they founded a school attended by the children of a number of nobles (Golitsins, Naryshkins, Apraksins, Dolgorukies, Golovkins, Musins-Pushkins, Kurakins).

After the first partition of the Commonwealth, the Jesuits reappeared in Russia, since their organizations existed on the territory of Belarus and Ukraine, which became part of the Russian Empire. About 20 Jesuit organizations came under Russian rule: 4 colleges (collegiums) - in Dinaburg, Vitebsk, Polotsk and Orsha, 2 residences - in Mogilev and Mstislavl and 14 missions; over 200 Jesuits (97 priests, about 50 students and 55 coadjutors). The property of the Jesuits was estimated at 20 million zlotys. Empress Catherine II decided to leave the Jesuits in Russia on the condition that they take the oath to the Empress.

In 1773, a bull was issued by Pope Clement XIV on the dissolution of the Jesuit order and the cessation of its existence. Empress Catherine II refused to recognize her and allowed the Jesuits to maintain their organization and possessions on the territory of the Russian Empire. At the end of the 18th century, Russia became the only state where the Jesuits received the right to operate. In 1779, despite the pope's protests, a Jesuit novitiate (educational institution) was opened in Polotsk.

In 1800, Emperor Paul I entrusted the Jesuits with educational activities in the western provinces of Russia, placing them at the head of the Vilna Academy. The favorite of Paul I was the Viennese Jesuit Gruber (since 1802, the general of the Jesuit order), who repeatedly talked with the emperor about the unification of the churches.

In 1812, at the initiative of Alexander I, the Polotsk College of Jesuits was transformed into an academy, received the rights of a university and the leadership of all Jesuit schools in Belarus. During the reign of Emperor Alexander I, the Jesuits launched a wide missionary activity in Russia. Jesuit missions were established in Astrakhan, Odessa, and Siberia. In 1814–1815, conversions to Catholicism became more frequent, especially after the official restoration of the order in 1814, and the protests of the Orthodox clergy against the activities of the Jesuits in Russia intensified.

The abolition of the order lasted for forty years. Colleges, missions were closed, various undertakings were stopped. The Jesuits were attached to the parish clergy (the clergy as a special class of the Church, distinct from the laity). However, for various reasons, the Society continued to exist in some countries: in China and India, where several missions were preserved, in Prussia and, above all, in Russia, where Catherine II refused to publish the decree of the pope. Much effort was made by the Jesuit Society on the territory of the Russian Empire so that it could continue to exist and operate.

The Society was re-established in 1814. Collegiums are experiencing a new flourishing. In the conditions of the “industrial revolution”, intensified work is being carried out in the field of technical education. When laity movements appear at the end of the 19th century, the Jesuits take part in leading them.

Intellectual activity continues, among other things, new periodicals are created. In particular, it is necessary to note the French magazine "Etudes", founded in 1856 by Father Ivan Xavier Gagarin. Public research centers are being created to study new social phenomena and influence them.

In 1903, the Jesuits formed the Action Populaire organization to help change social and international structures and help the working and peasant masses in their collective development. Many Jesuits are also engaged in fundamental research in the natural sciences, which are experiencing their rise in the 20th century. Of these scientists, the most famous paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. The Jesuits also work in the world of mass communication. By the way, they have been working at Vatican Radio since its foundation to the present day.

The Second World War became for the Society, as well as for the whole world, a period of transition. In the post-war period, new beginnings emerge. The Jesuits are involved in creating a "working mission": priests work in a factory to share the conditions in which the workers live and to make the Church present where it was not. Society has come to the need to modify its mode of activity. In 1965, the 31st General Congregation was convened, which elected a new General, Father Pedro Arrupe, and thought about some of the necessary changes. Ten years later, Father Pedro Arrupe decides to convene the 32nd General Congregation to think more deeply about the mission of the Society in today's world. This Congregation, having affirmed in its decrees the paramount importance of the mission of "service of faith", put forward another task - the participation of the Order in the struggle for justice in the world. And earlier, many members of the Society of Jesus, as if going beyond the usual limits of their already versatile calling, were included in various spheres of public activity to establish a more just social order and protect human rights. But what in the past was considered the work of individual members, now, after the official decrees of the Congregation, has become the ecclesiastical mission of the Order along with the mission of opposing atheism. Therefore, the 4th Decree adopted by this Congregation bears the title: "Our mission today: the service of the faith and the promotion of justice."

And today, the activities of the Jesuits are not limited to any particular field, although priority is given to pedagogical activities at all levels. In addition, they preach, lead spiritual institutions and parish life, engage in missionary work at home and abroad, scientific research, publication of newspapers addressed to the general readership and special religious magazines, television and radio activities, and they also work in the agricultural and technical schools established by the order. For the first time in the history of the Church, a religious order combined in its ministry two missions: the defense of faith and the defense of human dignity in all parts of the world, among all peoples, regardless of religion, culture, political system, race.

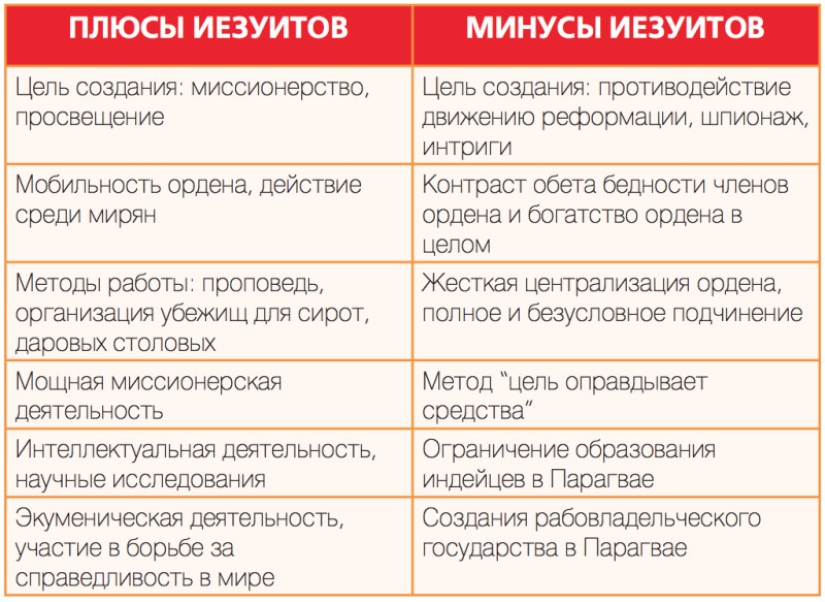

The mysterious and ambiguous history of the Jesuits. The order, which began with ten people, based on "gospel poverty" and "the return to the bosom of the church of the backsliders" changed the course of history. Yes, there were intrigues at the courts, but the “The end justifies the means” was used, and the Protestants were heretics for a long time. But... they not only built an education system, created periodicals, worked in various media, they carried, and still carry Christian values. And at the same time lay them in the foundation of the lives of children. The Jesuits, as missionaries, reached places where for a long time no one other than them from Christians reached. Yes, they had strict centralization and complete unconditional subordination, but they had an idea and a goal. They were not afraid of the changes that were taking place around them, the “Jesus society” was also changing then, the changes in the second half of the twentieth century especially show this.

Do we really have nothing to learn from them? Right now, when “agents of influence” of the ideas of homosexuality, permissiveness and tolerance penetrate into the education system, newspapers, magazines, television, cinema and literature, when they shoot at American schools, and Slavic teenagers can easily set fire to a passerby on “eternal fire”. And we won't do anything? We will not go to schools, we will not write books, we will not educate those who could just be in their place (at school, at university, in Hollywood, in parliament) and do their own thing, while not “flexing under a changing world”?

Recent articles

It's high time to admit that this whole hipster idea has gone too far. The concept has become so popular that even restaurants have ...

There is a perception that people only use 10% of their brain potential. But the heroes of our review, apparently, found a way to ...

New Year's is a time to surprise and delight loved ones not only with gifts but also with a unique presentation of the holiday ...