How people fought the heat before the era of air conditioners

Categories: History | North America

By Pictolic https://pictolic.com/article/how-people-fought-the-heat-before-the-era-of-air-conditioners.htmlEvery day, using many things that have long been familiar to us, we don't think much about where they came from, who invented them, who first started using them, how long ago it was and how we managed without them before.

Take, for example, an air conditioner. For people living in most of Russia, this household appliance may seem like a kind of luxury — with air conditioning, of course, it is more comfortable, but you can completely do without it. But for America, it became a device that changed the country. It is customary to talk about air conditioners as devices that cool the air, but the effect of their appearance extends much wider than temperature graphs. Thanks to air conditioners, the architecture of buildings, people's habitats and the way they live have changed. We can say that air conditioning has created a modern American way of life.

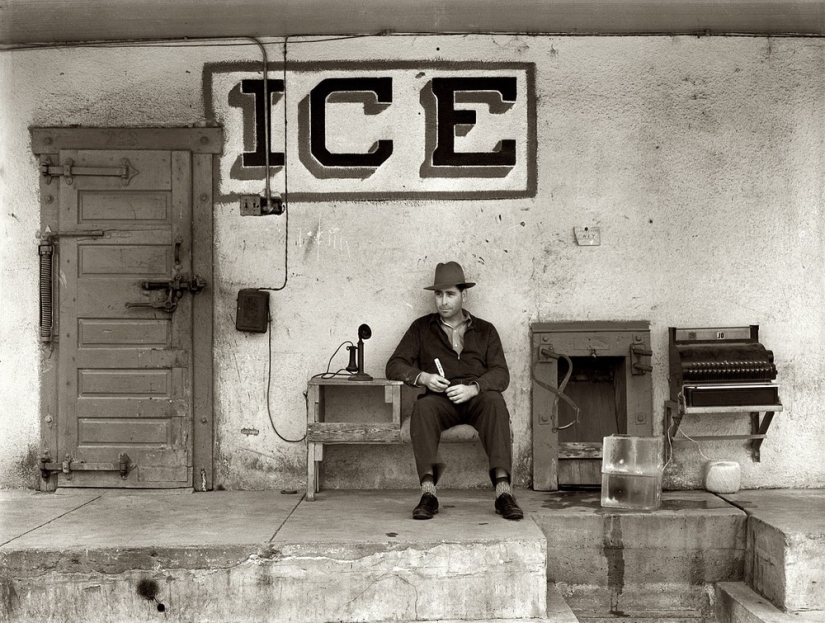

Before the advent of mechanical cooling devices, people were constantly inventing various options for how to reduce the temperature in their home. Unfortunately, most of them were either ineffective or very costly. Ice was actively used, but, as you understand, it was necessary to buy it regularly, which was not affordable for everyone.

Ice in winter was mined on frozen reservoirs in New England and shipped throughout the United States, as well as to the Caribbean and even India! Up to a certain point, the low population density, a large number of green spaces and the fact that many towns were located on the banks of large reservoirs saved. In addition, people were in no particular hurry to move to the hot southern states. This is also why almost all large American cities were built in the relatively comfortable northern part of America.

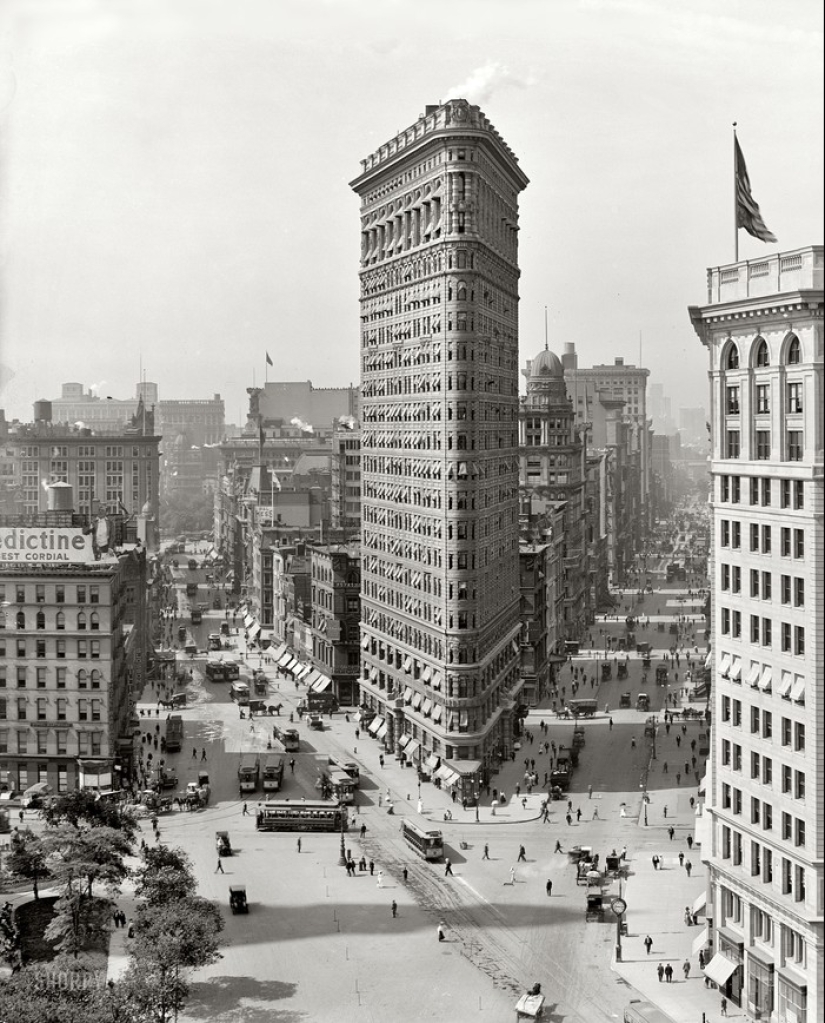

Look at any photo of New York at the beginning of the 20th century: a metropolis built up with high-rise buildings, paved streets, electric lighting, water supply system, sewerage, numerous shops and shops, working public transport, underground and aboveground subway lines, schools, libraries and so on, and coolness in the hot summer months was achieved only when with a piece of ice, an open window, and an electric fan. In addition, life was greatly complicated by the dress code adopted at that time. Long dresses for women, suits and mandatory hats for men. Unsurprisingly, many of them smelled quite strongly of sweat.

Air conditioning has changed American architecture. This was especially true for private housing construction. Before the advent of air conditioning, materials such as stone and brick were actively used in construction, which kept both heat and cold longer. The ceilings in the rooms were made higher so that hot air gathered overhead, leaving the inhabitants relatively cool below. Ceiling fans that appeared later helped to lift warm air up in summer and lower it down during winter.

Private houses were built mainly two-storeyed. Moreover, the bedrooms were always arranged on the upper floors and used them only at night, opening the windows wide open. All life took place on the ground floor. Windows were made, if possible, from all sides of the building to blow through the interior. Special opening windows were made above the interior doors, which improved the air circulation in the rooms.

Trees were always planted on the south side of the house to create shade. Moreover, in summer they served as a barrier to sunlight, and in winter, when the leaves fell, on the contrary, they were allowed into the room. The same applied to the widespread landscaping of city streets, which were planted with trees with spreading crowns that gave good shade. In buildings, the traction effect was actively used, making the stairs open and pulling hot air up and out through them. A small backyard, planted with trees, shrubs and plants, also had its own function. By opening and closing certain windows and doors, cool air from the backyard entered the house and hot air from the premises went outside. The windows were closed with shutters or thick curtains to prevent the heating of the walls of the room and furniture from sunlight. The houses necessarily had large covered terraces where they slept during the hot summer months.

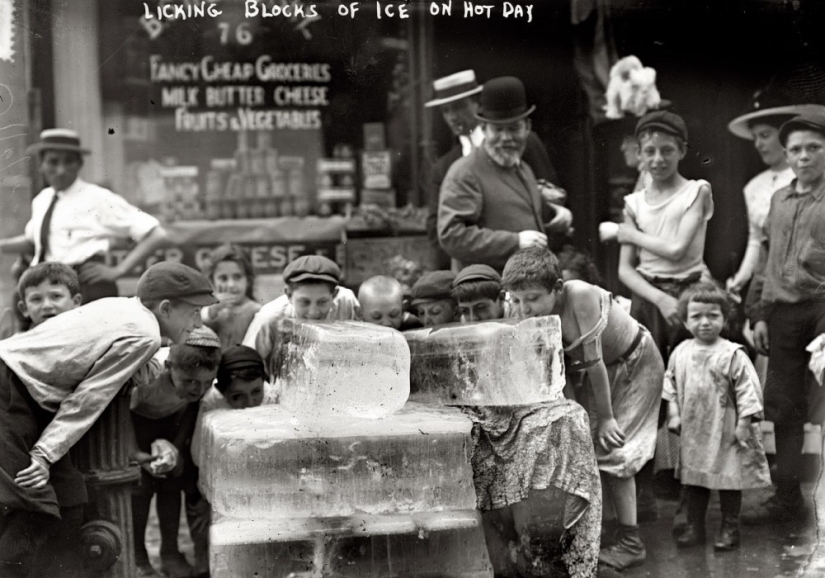

Urban residents had it worse. During the intense heat, they escaped in city pools and all available reservoirs. The beaches were crowded. They had to sleep on fire escapes or even on the street.

Fire hydrants in New York were intended not only to extinguish the fire, but also to cool its residents.

Old high-rise buildings have always had a complex U- or H-shaped shape so that all rooms inside have the maximum number of windows. Up until the 40s, the windows of many New York skyscrapers were equipped with awnings that closed the room from direct sunlight, and numerous fans buzzed inside, dispersing the humid and stuffy air.

Most cities in the south and many cities in the north of the United States died out during the summer months. People moved to live in other places. Many went to the ocean, the coast of which was built up with apartment hotels. The capital of the United States in the summer months turned into a ghost town.

In order to cool down a little, people were ready to ride for hours on double-decker buses with an open top or trams, the windows of which were either open or completely absent.

The man who changed America was 25-year-old Willis Carrier from Buffalo, New York, who worked as an engineer at the Buffalo Forge Company. Solving the problem of excessive humidity in the Brooklyn printing house in 1902, he assembled and installed in its basement a device that became the first air conditioner in history. But it was not the compact unit that we are used to today, but a huge mechanism that occupied almost the entire basement. In the same 1902, the air conditioning system was ordered by the New York Stock Exchange, which installed it no longer to solve production problems, but for the comfort of employees working in the building. Then it went-it went. The first office building with an air conditioning system was the Ermor Building in Kansas, Missouri, and each of his rooms was equipped with an individual thermostat.

The first device for cooling a private house appeared in 1914. It could not be called compact either. It was created by the same Carrier, and the first home air conditioner was installed in the mansion of Charles Gates, the son of tycoon John Gates, who made a fortune on barbed wire. The only funny thing was that the Gates mansion was located in the capital of Minnesota — Minneapolis — a city in the north of the United States with far from the hottest climate. For a long time, due to the high cost and huge dimensions, air conditioners were the lot of an exceptionally large business. They were installed in department stores, cinemas, hotels and similar places. In private homes, they were still quite rare for a very long time.

The first cinema with an air conditioning system was the New York "Rivoli", owned by the famous Paramount Pictures. In 1925, at Carrier's suggestion, it was equipped with air conditioning, and ticket sales increased several times. The fact is that all cinemas, without exception, experienced problems during the hot summer months. The audience did not want to sit in stuffy enclosed spaces, which is why even the most popular films were shown in half-empty halls, and cinemas suffered heavy losses. The problems disappeared with the advent of air conditioning, and cinemas began to fill up, as people began to go there not only to watch a movie, but also to just sit in the cool. This, in turn, changed the time of the premieres of films and the schedule of their releases. Many paintings began to appear on screens in the summer, during an active pilgrimage to the cinema. The advantage of air conditioning has become so obvious that in just five years Carrier's air conditioning systems have been installed in more than 300 cinemas across the country. Offices, shops, hospitals, factories, railway cars, etc. were equipped with air conditioners. They improved conditions and increased labor productivity in the summer months. Air conditioners made it possible to travel with great comfort and live comfortably where it was impossible to live before.

In 1931, the first window air conditioner appeared. Everything would be fine, but it only cost more than some houses. These devices became more or less mass-produced only in the 50s of the last century, and until that time America, and the rest of humanity, somehow managed without them. The advent of affordable air conditioners revolutionized the real estate market and changed the demographics of the country. The outflow of population from the southern states, which lasted throughout the first half of the 20th century, was replaced by a rapid increase. The active settlement of Florida, California, Texas, Georgia, New Mexico and other states of the "Sun Belt" of the USA began. The land around big cities began to be massively built up with inexpensive wooden houses equipped with window blocks, which, combined with other reasons, led to mass migration of the population to the suburbs and changed America forever. People began to spend more time at home, and television finally tied them to the sofa. Vacation on the ocean from seasonal at first turned into a week, and then completely reduced to a few days. The need to move to the ocean coast during the hot months disappeared, which led to the decline and closure of many American resorts such as Coney Island and Atlantic City. At the same moment, cars, planes and air conditioners made holidays available in new places like Florida, Mexico or the Caribbean.

The owners of the fan blog of The New Yorker magazine newyorker_ru have translated a wonderful essay by Arthur Miller, telling about how life was in the days before air conditioners.

I don't remember exactly what year it was — in 1927 or 1928, the heat was just crazy in September. It did not subside even after the start of the school year — we just returned from our dacha to Rockaway Beach. All windows in New York was wide open, and there were a lot of shopping carts on the streets where you could buy crushed ice or sprinkled colored sugar for a couple of pennies. As children, we jumped behind these slowly rolling horse-drawn carts and stole one or two pieces of ice; the ice smelled a little like manure, but refreshed the palms and mouth.

People west of 110th Street, where I lived, were too well-off to sit on their fire escapes, but from the corner of 111th and beyond, as soon as night fell, people took out mattresses and whole families, in their underwear, settled on their iron balconies.

Even at night the heat did not subside. With a couple of other children, I walked along 110th to the Park and strolled among hundreds of people who, alone or in families, were sleeping right on the grass, next to large alarm clocks that performed a quiet cacophony - some clocks syncopated with others. Children were crying in the dark, men were whispering in low voices, and somewhere near the lake a sudden female laughter could be heard. I can only remember white people lying on the grass; Harlem then began at 116th Street.

Later, in the 30s, during the Great Depression, the summer months seemed even hotter. In the West, it was a time of hot sun and sandstorms, when entire farms suffering from drought were removed from their homes. Okies (residents of Oklahoma), immortalized by Steinbeck, made their desperate rushes to the Pacific Ocean. My father then had a small coat-making factory on 39th Street, where about a dozen men worked on sewing machines. Even watching them working with thick wool winter coats in this heat was torture for me. The cutters received a piecework salary — only the finished number of stitches was paid, so their lunch break was very short — fifteen or twenty minutes. They brought food with them: a bunch of radishes, tomatoes, cucumbers and a jar of thick sour cream. They cut all this into their bowls stored under the machines. Also, a slice of bread made of coarse unseeded rye flour appeared from somewhere, which they tore apart and wielded like a spoon, scooping vegetables with sour cream.

Men were constantly sweating, and I remember one employee whose sweat dripped in an extremely original way. He was a tiny kid who neglected scissors in his work and at the end of each seam always bit off the thread instead of cutting it, so that the remnants of the threads stuck to his lower lip, and by the end of the working day he had a colorful beard of threads. His sweat flowed along these broken threads and dripped onto the cloth, which he constantly wiped with a rag.

Considering the heat, people certainly smelled, but some smelled much stronger than others. One of the cutters smelled like a horse, and my father, who, as a rule, did not distinguish smells (no one understood why), claimed that he could smell this man, and always addressed him from a decent distance. In order to earn as much money as possible, this cutter worked from 5:30 in the morning until midnight. He had several apartments in the Bronx, and also owned land in Florida and Jersey—he looked like a greedy half-crazy guy. He had a powerful build, a straight posture, whipped hair on his head and black shadows on his cheeks. He snorted like a horse, pushing the pattern cutter through about eighteen layers of material. One late evening, he squeezed his eyes shut from the corrosive sweat, holding the material with his left hand and pressing on the vertical, razor-sharp blade moving back and forth with his right hand. The blade sliced through his index finger in the area of the second phalanx. He angrily muttered that he would not go to the hospital, put his hand with the stump under the water tap, then wrapped his hand in a towel and returned to the machine again, snorting and stinking. When the blood seeped through the towel, my father knocked out his machine and ordered him to go to the hospital. But the next morning he was already at his workplace and worked again from early morning until late at night, as usual, accumulating money for new apartments.

At that time there were still trains running along 2nd, 3rd, 6th and 9th Avenues, and many cars were made of wood, with windows that, of course, were open. There were open trams running along Broadway without side walls, in which you could at least catch a breeze, even if it was warm. Desperate people, unable to withstand the heat in their apartments, paid 5 cents and rode aimlessly for a couple of hours on the tram to cool off a little. As for Coney Island, every stretch of beach was so packed with people for the weekend that it was almost impossible to find a place to sit down, put your book or a hot dog.

I first encountered air conditioning in the 60s when I stayed at the Chelsea Hotel. The so-called hotel management installed an air conditioner on wheels, which rather pointlessly cooled and sometimes heated the air, depending on how many jugs of water were poured into it. When it was initially filled with water, it started spraying water all over the room, so you had to turn it to face the bathroom, not the bed.

A gentleman from South Africa once told me that in New York is hotter in August than in any other place he knows in Africa, but for some reason people here are dressed like in a northern city. He wanted to put on shorts, but was afraid that he would be arrested for indecent behavior.

The terrible heat created illogical solutions: linen suits, on which deep folds remained after someone bent an arm or leg; men's straw hats, stiff as matzo, similar to the stiff yellow flowers that bloomed annually throughout the city in the first days of June. Hats left deep red dents on men's foreheads, and wrinkled suits, which should not have been so hot, had to be adjusted down, up, or sideways all the time to allow the body to breathe.

In summer, the city floated as if in a fog, in which particularly susceptible people endlessly repeated a stupid greeting: "It's a little hot, huh? haha." It was like the last joke before the world melts into an ocean of sweat.

Arthur Miller

Recent articles

It's high time to admit that this whole hipster idea has gone too far. The concept has become so popular that even restaurants have ...

There is a perception that people only use 10% of their brain potential. But the heroes of our review, apparently, found a way to ...

New Year's is a time to surprise and delight loved ones not only with gifts but also with a unique presentation of the holiday ...