"Evaporating people" — what the Japanese are doing to wash away the shame from their family

After getting married, martial arts master Ichiro was optimistic about making plans for the future. Together with his wife Tomoka, they lived in their own house in Saitama, a prosperous suburb of Tokyo. Their first child Tim was born. The family took out a loan to open a dumpling shop. But suddenly there was a default, and the couple found themselves in debt. They did what hundreds of thousands of Japanese do in similar circumstances: they sold their house, packed up their belongings and disappeared. Forever.

Of the many oddities that are inherent in Japanese culture, the phenomenon of "evaporating people" remains little known. Since the mid-1990s, approximately 100,000 Japanese have disappeared in the country every year. They expel themselves from society because of the humiliations they have experienced on a different scale: divorce, debt, dismissal from work, a failed exam.

French journalist Lena Mauger found out about this in 2008 and spent five years researching the phenomenon of "evaporating people", telling stories of Japanese residents that she herself could not believe.

These lost people live in ghost towns that they built themselves.

The city of Sanya is not marked on any map. From a technical point of view, it does not exist at all. These are slums within Tokyo, the existence of which the authorities prefer to keep silent. The territory is under the control of the Yakuza, a criminal organization that hires people to perform illegal work. The "evaporated" live in tiny, squalid hotel rooms, often with shared toilets and no internet access. In most of these hotels it is forbidden to talk after six in the evening.

Here Mauger met Norihiro, a 50-year-old man who arranged his disappearance 10 years ago. He cheated on his wife, but the real shame for the man was that he lost his job as an engineer. Out of shame, he couldn't tell his family about it. During the week, Norihiro behaved the same as usual: he got up early in the morning, put on a suit and tie, took a briefcase, kissed his wife goodbye, then drove to the office building of his former job and sat in the car all day, did not eat anything and did not talk to anyone. The fear that his lie would be revealed was unbearable.

On payday, he put on clean, ironed clothes and boarded a train towards Sanya. He did not leave any note to the family, and all his relatives believe that the man went to the Aokigahara forest, where he committed suicide.

Today he lives under a false name, in a windowless room, and locks the door with a padlock. He drinks and smokes a lot. Practicing such a masochistic form of punishment, the man decided to live out the rest of his days. "After all these years, I could come back. But I don't want my loved ones to see me in this state. Look at me. I look like a jerk. I am nothing. If I die tomorrow, I don't want to be identified," Norihiro admits.

Yuichi is a former construction worker who disappeared in the mid—1990s. He was supposed to take care of a sick mother, but went bankrupt because of the cost of medicines for her.

Yuichi checked his mother into a cheap hotel room and left her there. His act may seem paradoxical, even perverse, but not for Japanese culture, in which suicide is considered the most worthy way to erase the shame that has fallen on the family.

The most cases of "evaporation" in Japan were after two key events: the defeat in The Second World War, when the whole country experienced a sense of national shame, and during the financial crises of 1989 and 2008.

Underground organizations began to appear to provide services to those who wanted to pass off their disappearance as a kidnapping. The houses of these people were vandalized to make everything look like a robbery, they were given false documents so that they could not be traced.

One of these organizations was the company "Night Crossings", which was opened by Shu Hatori. He was engaged in a legal business — furniture transportation — until one day a woman approached him with a question, could he help her "disappear with the furniture". She complained that her husband's debts made life unbearable.

Hatori charged 3.4 thousand dollars for his services. He faced different clients: with housewives who have spent all their family savings, with wives whose husbands have left, and even with students who are tired of living in a dormitory.

When Hatori was a child, his parents also ran away, finding themselves in debt. He believed that he was doing a good deed by helping those who turned to him: "People often call it cowardice, but over the years I've realized that it's only good for everyone." In the end, Hatori gave up this activity — however, he refused to share the details of such a decision.

Hatori was a consultant on the set of the Japanese television series "Night Flight". A telenovela based on real cases of disappearances became a hit in the late 1990s. In the center of the plot was the organization "Rising Sun", the prototype for which was the company Hatori.

Here is an excerpt from the description of the series:

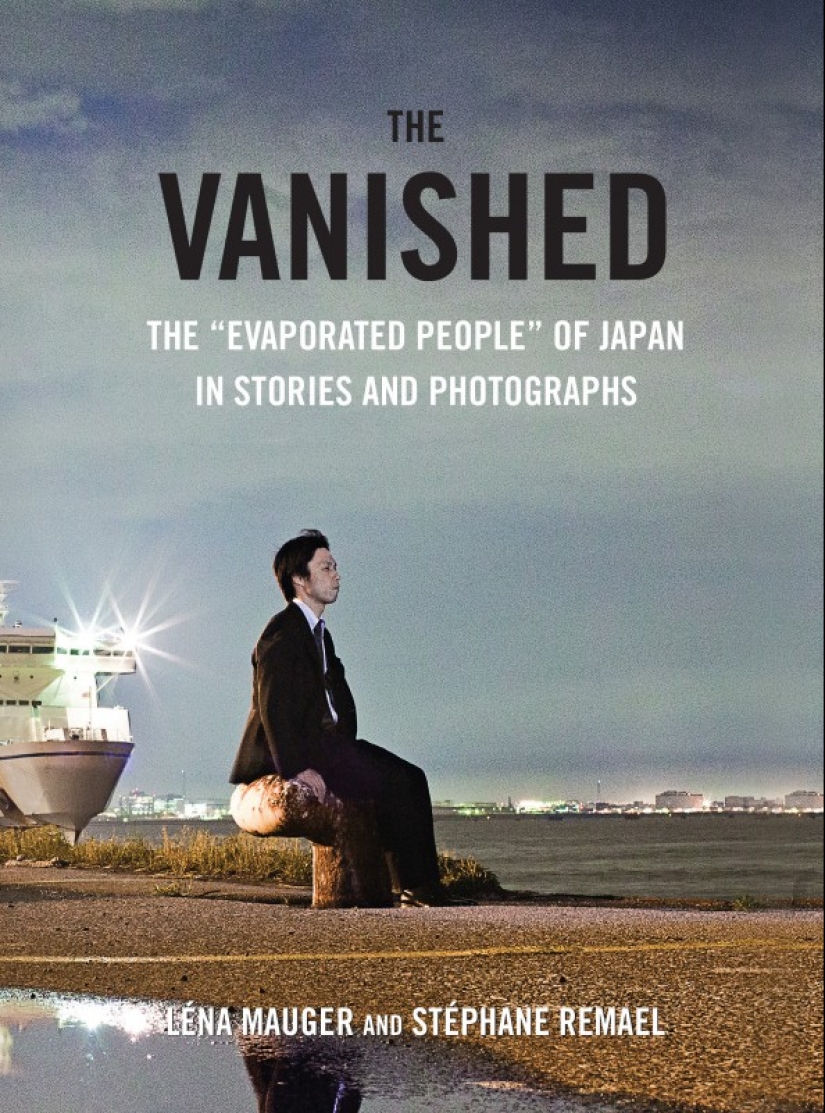

A book about the disappeared, prepared by journalist Lena Mauger and photographer Stefan Remael.

Regardless of the reasons for the shame that forces the Japanese to "evaporate", it does not make it easier for their families. Many relatives are so ashamed that their loved one has disappeared that, as a rule, they do not even report it to the police.

Those families who are trying to find the "disappeared" turn to a private organization that keeps all the information of its clients secret. The company's address is difficult to find, and its headquarters is a tiny office with one desk and walls yellowed from cigarette smoke.

The organization consists of a network of private investigators, many of whom have personally experienced the disappearance or suicide of loved ones, and therefore work for free. On average, they investigate about 300 cases annually. Their work is complicated by the fact that in Japan there is no state database with data on missing people. Citizens of the country do not have documents with an identification number, such as a social insurance number or passport, which would allow tracking a person's movements around the country. The Japanese police also do not have access to information about banking transactions.

This is an unaffordable amount for those whose loved one ran away because of debts. People who "evaporate" often change their names and appearance. Others just think that no one will look for them.

Sakae managed to find a young man who once did not return home after the exam. A friend accidentally noticed him in the southern part of Tokyo. Sakae wandered the streets until he found this young man, who, according to him, was shaking with shame. The young man was afraid that he would disappoint his family, because he did not pass the exam. He was visited by thoughts of suicide, but he could not commit suicide.

Now Sakae is investigating the disappearance of the mother of an eight-year-old disabled boy. She "disappeared" on the day of her son's performance at the school play, despite her promise to sit in the front row. No one has seen her since. The son and husband of the missing woman do not find a place for themselves: the woman has never let anyone know that she is unhappy, suffering or regretting any of her actions.

Sakae does not lose hope of finding her. "She is a mother," he says. "Perhaps fate will lead her back to her loved ones."

According to a 2014 World Health Organization report, the suicide rate in Japan is 60 percent higher than the world average. There are 60 to 90 suicides per day in the country. The centuries-old practice of depriving oneself of life dates back to the samurai who did hara-kiri, or kamikaze, to military pilots during the Second World War.

Japanese culture also emphasizes the superiority of the group over the individual. "A protruding nail needs to be driven in" is a Japanese maxim. Those who cannot or do not want to fit into society and adhere to its rigid norms and fanatical diligence, it remains to "evaporate" in order to gain a kind of freedom.

For young Japanese people who want to live differently, but do not want to break off relations with loved ones, there is a compromise solution: to become an otaku, that is, periodically escape from reality, dressing up as a favorite anime character.

Recent articles

It's high time to admit that this whole hipster idea has gone too far. The concept has become so popular that even restaurants have ...

There is a perception that people only use 10% of their brain potential. But the heroes of our review, apparently, found a way to ...

New Year's is a time to surprise and delight loved ones not only with gifts but also with a unique presentation of the holiday ...