Aivazovsky without the sea. Unknown paintings of the great marine painter

Categories: Culture

By Pictolic https://pictolic.com/article/aivazovsky-without-the-sea-unknown-paintings-of-the-great-marine-painter.htmlThe sea and Aivazovsky have been synonymous for a century and a half. We say “Aivazovsky” - we imagine the sea, and when we see a sea sunset or storm, a sailboat or foaming surf, calm or sea breeze, we say: “Pure Aivazovsky!”

It's hard not to recognize Aivazovsky. But today we will show you a rare and little-known Aivazovsky. Aivazovsky unexpected and unusual. Aivazovsky, whom you may not even immediately recognize. In short, Aivazovsky without the sea.

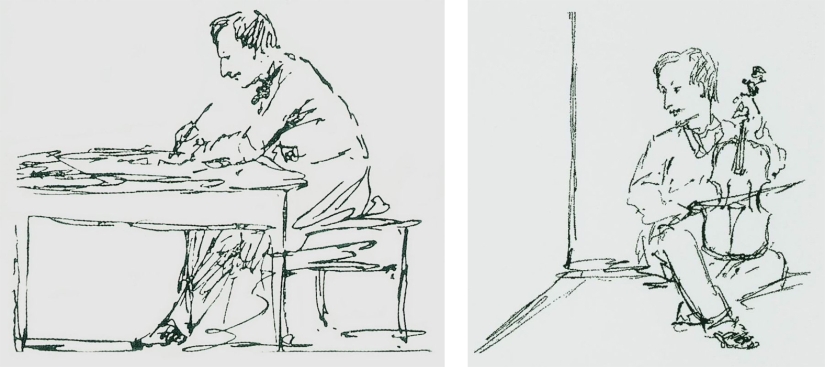

These are graphic self-portraits of Aivazovsky. Perhaps he is unrecognizable here. And he looks more like not his own picturesque images (see below), but his good friend, with whom he traveled around Italy in his youth - Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol. The self-portrait on the left is like Gogol, composing “Dead Souls” at a table littered with drafts.

Even more interesting is the self-portrait on the right. Why not with a palette and brushes, but with a violin? Because the violin was Aivazovsky’s faithful friend for many years. No one remembered who gave it to 10-year-old Hovhannes, a boy from a large and poor family of Armenian immigrants in Feodosia. Of course, parents couldn’t afford to hire a teacher. But that wasn't necessary. Hovhannes was taught to play by traveling musicians at the Feodosia bazaar. His hearing turned out to be excellent. Aivazovsky could pick out any tune, any melody by ear.

The aspiring artist brought his violin with him to St. Petersburg and played “for the soul.” Often at a party, when Hovhannes made useful acquaintances and began to visit society, he was asked to play the violin. Possessing an easy-going character, Aivazovsky never refused. In the biography of composer Mikhail Glinka, written by Vsevolod Uspensky, there is the following fragment:

Aivazovsky will take his violin with him everywhere. On the ships of the Baltic squadron, his playing entertained the sailors; the violin sang to them about warm seas and a better life. In St. Petersburg, seeing his future wife Julia Grevs for the first time at a social reception (she was just the governess of the master's children), Aivazovsky did not dare to introduce himself - instead, he would again pick up the violin and belt out a serenade in Italian.

An interesting question: why in the picture Aivazovsky does not rest the violin on his chin, but holds it like a cello? Biographer Yulia Andreeva explains this feature as follows:

And this self-portrait of Aivazovsky is just for comparison: unlike the not so widely known previous ones, the reader is probably familiar with it. But if in the first ones Aivazovsky reminded me of Gogol, then in this one, with well-groomed sideburns, he reminded me of Pushkin. By the way, this was precisely the opinion of Natalya Nikolaevna, the poet’s wife. When Aivazovsky was presented to the Pushkin couple at an exhibition at the Academy of Arts, Natalya Nikolaevna kindly noted that the artist’s appearance very much reminded her of the portraits of young Alexander Sergeevich.

At the first (and if we discard the legends, then the only) meeting, Pushkin asked Aivazovsky two questions. The first is more than predictable when you meet someone: where is the artist from? But the second one is unexpected and even somewhat familiar. Pushkin asked Aivazovsky if he, a southern man, was not freezing in St. Petersburg? If only Pushkin knew how right he turned out to be. All the winters at the Academy of Arts, young Hovhannes was indeed catastrophically cold.

There are drafts in the halls and classrooms, teachers wrap their backs in down scarves. 16-year-old Hovhannes Aivazovsky, accepted into the class of Professor Maxim Vorobyov, has numb fingers from the cold. He is chilly, wraps himself in a paint-stained jacket that is not warm at all, and coughs all the time.

It is especially difficult at night. A moth-eaten blanket does not allow you to warm up. All members are chilled, tooth does not touch tooth, and for some reason the ears are especially cold. When the cold prevents you from sleeping, student Aivazovsky remembers Feodosia and the warm sea.

Staff doctor Overlach writes reports to the President of the Academy Olenin about Hovhannes’s unsatisfactory health:

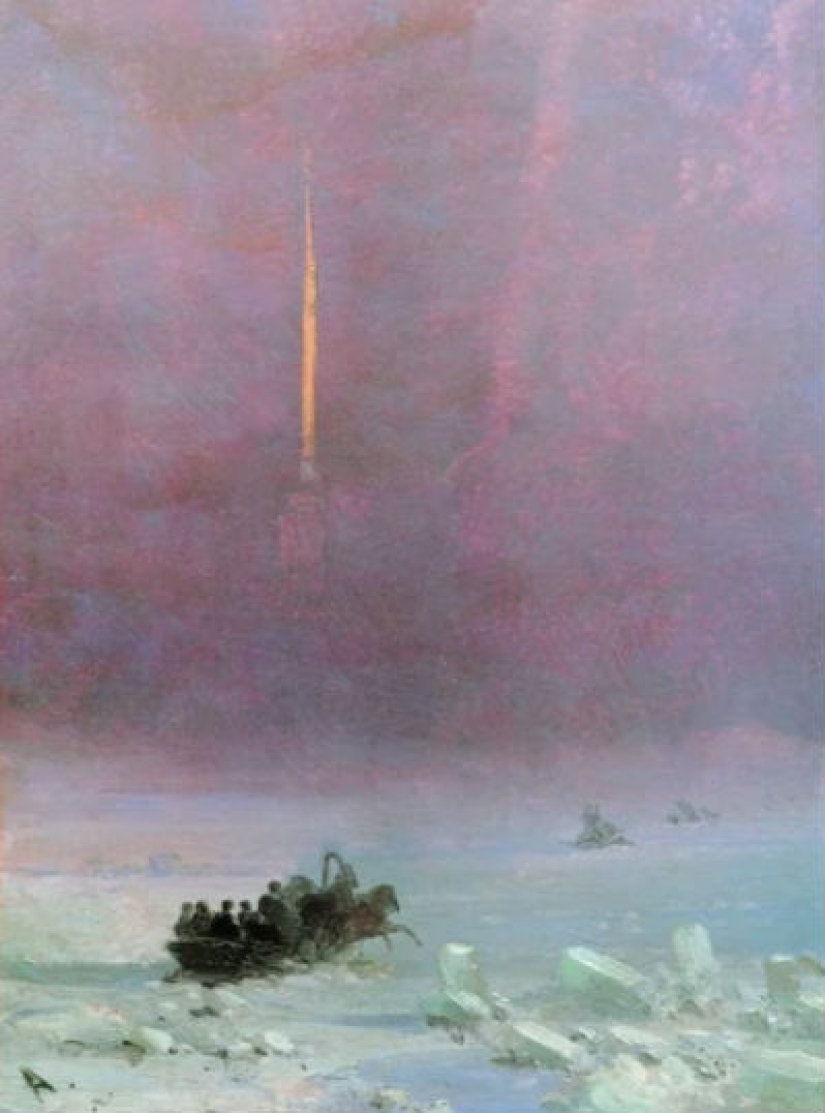

Is this why “Crossing the Neva,” a rare St. Petersburg landscape for Aivazovsky’s work, looks like it makes your teeth ache from the imaginary cold? It was written in 1877, the Academy is long gone, but the feeling of the piercing cold of Northern Palmyra remains. Giant ice floes rose on the Neva. The Admiralty Needle appears through the cold, hazy colors of the purple sky. It's cold for the tiny people in the cart. It’s chilly, alarming, but also fun. And it seems that there is so much new, unknown, interesting - there, ahead, behind the veil of frosty air.

The State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg carefully preserves Aivazovsky’s sketch “The Betrayal of Judas.” It is made on gray paper with white and Italian pencil. In 1834, Aivazovsky was preparing a painting on a biblical theme on the instructions of the Academy. Hovhannes was quite secretive by nature, loved to work alone and did not understand at all how his idol Karl Bryullov was able to write in front of any crowd of people.

Aivazovsky, on the contrary, preferred solitude for his work, so when he presented “The Betrayal of Judas” to his comrades at the academy, it came as a complete surprise to them. Many simply could not believe that a 17-year-old provincial, only in his second year of study, was capable of such a thing.

And then his ill-wishers came up with an explanation. After all, Aivazovsky always disappears from the collector and philanthropist Alexei Romanovich Tomilov? And in his collection there are Bryullovs, Poussins, Rembrandts, and who knows who else. Surely the cunning Hovhannes simply copied a painting there by some little-known European master in Russia and passed it off as his own.

Fortunately for Aivazovsky, the president of the Academy of Arts, Alexei Nikolaevich Olenin, had a different opinion about “The Betrayal of Judas.” Olenin was so impressed by Hovhannes’ skill that he honored him with high favor - he invited him to stay with him at the Priyutino estate, where Pushkin and Krylov, Borovikovsky and Venetsianov, Kiprensky and the Bryullov brothers visited. An unheard of honor for a novice academician.

By 1845, 27-year-old Aivazovsky, whose seascapes were already resounding throughout Europe from Amsterdam to Rome, was being paid tribute in Russia. He receives “Anna on the Neck” (Order of St. Anne, 3rd degree), the title of academician, 1,500 acres of land in Crimea for 99 years of use, and most importantly, an official naval uniform. The Naval Ministry, for services to the Fatherland, appoints Aivazovsky as the first painter of the Main Naval Staff. Now Aivazovsky is required to be allowed into all Russian ports and onto all ships, wherever he wishes to go. And in the spring of 1845, at the insistence of Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich, the artist was included in Admiral Litke’s naval expedition to Turkey and Asia Minor.

By that time, Aivazovsky had already traveled all over Europe (his foreign passport had more than 135 visas, and customs officers were tired of adding new pages to it), but had not yet been to the lands of the Ottomans. For the first time he sees Chios and Patmos, Samos and Rhodes, Sinop and Smyrna, Anatolia and the Levant. And what impressed him most was Constantinople:

“Coffee shop at the Ortakoy Mosque” is one of the views of Constantinople painted by Aivazovsky after this first trip. In general, Aivazovsky’s relations with Turkey are a long and difficult story. He will visit Turkey more than once. The artist was greatly appreciated by the Turkish rulers: in 1856, Sultan Abdul-Mecid I awarded him the Order of Nitshan Ali, 4th degree, and in 1881, Sultan Abdul-Hamid II awarded him a diamond medal. But between these awards there was also the Russian-Turkish War of 1877, during which Aivazovsky’s house in Feodosia was partially destroyed by a shell. However, it is significant that the peace treaty between Turkey and Russia was signed in a hall decorated with paintings by Aivazovsky. When visiting Turkey, Aivazovsky communicated especially warmly with the Armenians living in Turkey, who respectfully called him Aivaz Effendi. And when in the 1890s the Turkish Sultan committed a monstrous massacre in which thousands of Armenians died, Aivazovsky defiantly threw the Ottoman awards into the sea, saying that he advised the Sultan to do the same with his paintings.

Aivazovsky’s “Coffee House at the Ortakoy Mosque” is an ideal image of Turkey. Ideal - because it is peaceful. Sitting relaxing on embroidered pillows and immersed in contemplation, Turks drink coffee, inhale hookah smoke, and listen to unobtrusive melodies. Molten air flows. Time flows between your fingers like sand. No one is in a hurry - there is no need to rush: everything necessary for the fullness of being is already concentrated in the present moment.

It cannot be said that Aivazovsky in the landscape “Windmills in the Ukrainian steppe...” is unrecognizable. A wheat field in the sunset rays is almost like the rippling surface of the sea, and the mills are the same frigates: in some the wind inflates the sails, in others it rotates the blades. Where and, most importantly, when could Aivazovsky take his mind off the sea and become interested in the Ukrainian steppe?

Perhaps when he moved his family from Feodosia to Kharkov for a short time? And he didn’t transport it idly, but hastily evacuate it. In 1853, Turkey declared war on Russia, in March 1854 England and France joined it - the Crimean War began. In September the enemy was already in Yalta. Aivazovsky urgently needed to save his relatives - his wife, four daughters, and old mother.

The biographer writes that in the new place, Aivazovsky’s wife Yulia Grevs, who had previously actively helped her husband in Crimea in his archaeological excavations and ethnographic research, “tried to captivate Aivazovsky with archeology or scenes of Little Russian life.” After all, Julia really wanted her husband and father to stay with the family longer. It didn’t work out: Aivazovsky rushed to besieged Sevastopol. For several days under bombardment, he painted naval battles from life, and only a special order from Vice Admiral Kornilov forced the fearless artist to leave the theater of military operations. Nevertheless, Aivazovsky’s legacy includes quite a lot of ethnographic-genre scenes and Ukrainian landscapes: “Chumaks on Vacation,” “Wedding in Ukraine,” “Winter Scene in Little Russia” and others.

Aivazovsky left relatively few portraits. But he wrote to this gentleman more than once. However, this is not surprising: the artist considered Alexander Ivanovich Kaznacheev his “second father.” When Aivazovsky was still small, Kaznacheev served as the mayor of Feodosia. At the end of the 1820s, he increasingly began to receive complaints: someone was playing pranks in the city - painting fences and whitewashed walls of houses. The mayor went to inspect the art. On the walls were figures of soldiers, sailors and silhouettes of ships, induced by samovar coal - I must say, very, very believable. After some time, city architect Koch informed Treasurer that he had identified the author of this “graffiti.” It was 11-year-old Hovhannes, the son of the market elder Gevork Gaivazovsky.

“You draw beautifully,” Kaznacheev agreed upon meeting the “criminal,” “but why on other people’s fences?!” However, he immediately understood: the Aivazovskys are so poor that they cannot buy drawing supplies for their son. And Kaznacheev did it himself: instead of punishment, he gave Hovhannes a stack of good paper and a box of paints.

Hovhannes began to visit the mayor’s house and became friends with his son Sasha. And when in 1830 Kaznacheev became the governor of Tavria, he took Aivazovsky, who had become a member of the family, to Simferopol so that the boy could study at the gymnasium there, and three years later he made every effort to ensure that Hovhannes was enrolled in the Imperial Academy of Arts.

When the grown and famous Aivazovsky returns to live in Crimea forever, he will maintain friendly relations with Alexander Ivanovich. And even in a sense, he will imitate his “said father”, intensively caring for the poor and disadvantaged and founding the “General Workshop” - an art school for local talented youth. And Aivazovsky, using his own design and at his own expense, will erect a fountain in honor of Kaznacheev in Feodosia.

On November 17, 1869, the Suez Canal was opened for navigation. Laid through the Egyptian deserts, it connected the Mediterranean and Red Seas and became a conditional border between Africa and Eurasia. The inquisitive and still greedy for impressions 52-year-old Aivazovsky could not miss such an event. He came to Egypt as part of the Russian delegation and became the first marine painter in the world to paint the Suez Canal.

“Those paintings in which the main force is the light of the sun... should be considered the best,” Aivazovsky was always convinced. And there was just an abundance of sun in Egypt - just work. Palm trees, sand, pyramids, camels, distant desert horizons and “Caravan in an Oasis” - all this remains in Aivazovsky’s paintings.

The artist also left interesting memories of the first meeting of Russian song and the Egyptian desert: “When the Russian steamship was entering the Suez Canal, the French steamer ahead of it ran aground, and the swimmers were forced to wait until it was removed. This stop lasted about five hours.

It was a beautiful moonlit night, lending some kind of majestic beauty to the deserted shores of the ancient land of the pharaohs, cut off from the Asian shore by a canal.

To shorten the time, the passengers of the Russian ship staged an impromptu vocal concert: Mrs. Kireeva, possessing a beautiful voice, took on the duties of lead singer, a well-organized choir took up...

And so, on the shores of Egypt, a song sounded about “Mother Volga,” about the “dark forest,” about the “open field,” and rushed along the waves, silvered by the moon, shining brightly at the border of two parts of the world...”

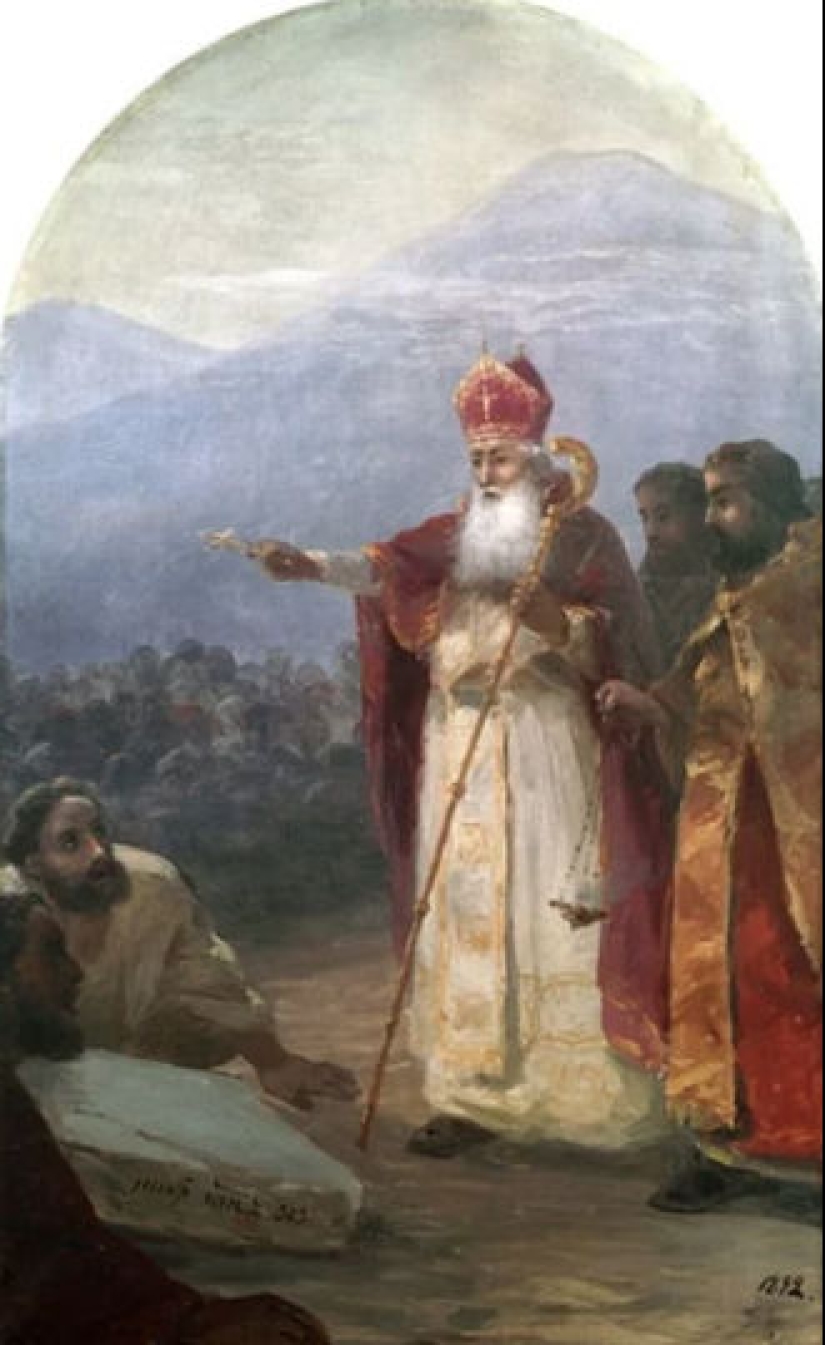

Perhaps it will be new to someone to learn that Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky was a true zealot of the Armenian Apostolic Church, one of the oldest, by the way, Christian churches. There was an Armenian Christian community in Feodosia, and the Synod was located in the “heart of Armenia” - the city of Etchmiadzin.

Aivazovsky's elder brother Sargis (Gabriel) became a monk, then an archbishop and an outstanding Armenian educator. For the artist himself, his religious affiliation was by no means an empty formality. He informed the Etchmiadzin Synod about the most important events of his life, for example about his wedding:

When family life goes wrong, Aivazovsky will have to seek permission to dissolve the marriage there.

In 1895, a distinguished guest came to Feodosia to visit Aivazovsky - Katalikos Khrimyan, the head of the Armenian Church. Aivazovsky took him to Old Crimea, where he erected a new one on the site of destroyed churches and even painted an altar image for it. At a gala dinner for 300 people in Feodosia, the Catholicos promised the artist:

In five years, 82-year-old Aivazovsky will be dead. His grave in the courtyard of the ancient temple is decorated with an inscription in Armenian: “Born mortal, he left behind an immortal memory.”

It would be unfair to the reader to end our story about Aivazovsky’s paintings, where the sea is absent, with the fact of the artist’s death. Moreover, having touched on many important biographical milestones, we still didn’t talk about love.

When Aivazovsky was no less than 65 years old, he fell in love. Moreover, he fell in love like a boy - at first sight and in circumstances that were least conducive to romance. He was riding in a carriage along the streets of Feodosia and crossed paths with a funeral procession, which included a beautiful young woman dressed in black. The artist believed that in his native Feodosia he knew everyone by name, but it was as if he had seen her for the first time and had no idea who she was related to the deceased - daughter, sister, wife. I made inquiries: it turned out that she was a widow. 25 years. Name is Anna Sarkizova, nee Burnazyan.

The late husband left Anna an estate with a marvelous garden and great wealth for the Crimea - a source of fresh water. She is a completely wealthy, self-sufficient woman, and also 40 years younger than Aivazovsky. But when the artist, trembling and not believing in possible happiness, proposed to her, Sarkizova accepted him.

A year later, Aivazovsky confessed to a friend in a letter:

They will live 17 years in love and harmony. As in his youth, Aivazovsky will write a lot and incredibly productively. And he will also have time to show his beloved the ocean: in the 10th year of marriage they will sail to America via Paris, and, according to legend, this beautiful couple will often be the only people on the ship who are not susceptible to seasickness. While most of the passengers, hiding in their cabins, waited out the rolling and storm, Aivazovsky and Anna serenely admired the expanses of the sea.

After Aivazovsky’s death, Anna would become a voluntary recluse for more than 40 years (and she would live until she was 88): no guests, no interviews, much less attempts to arrange her personal life. There is something strong-willed and at the same time mysterious in the look of a woman whose face is half hidden by a gauze veil, so similar to the translucent surface of water from the seascapes of her great husband, Ivan Aivazovsky.

Recent articles

It's high time to admit that this whole hipster idea has gone too far. The concept has become so popular that even restaurants have ...

There is a perception that people only use 10% of their brain potential. But the heroes of our review, apparently, found a way to ...

New Year's is a time to surprise and delight loved ones not only with gifts but also with a unique presentation of the holiday ...