Evolutionary Atavisms: 7 Organs We No Longer Need

Categories: Health and Medicine | Nature | Science

By Pictolic https://pictolic.com/article/evolutionary-atavisms-7-organs-we-no-longer-need.htmlOur body is a real time machine, in which relics of the past are hidden. The appendix, goose bumps, and even wisdom teeth - these and other organs today seem unnecessary, but they once played an important role in the survival of our ancestors. Why did evolution not rid us of them? Find out which body parts we wear as a reminder of our past!

Thanks to evolution, living organisms on our planet have adapted to their environment for millions of years. Humans were no exception and gradually changed to survive as a species. At the same time, evolution left us some organs that we have not used for a long time. There are not many of them, but some of them are not only useless, but also cause us trouble.

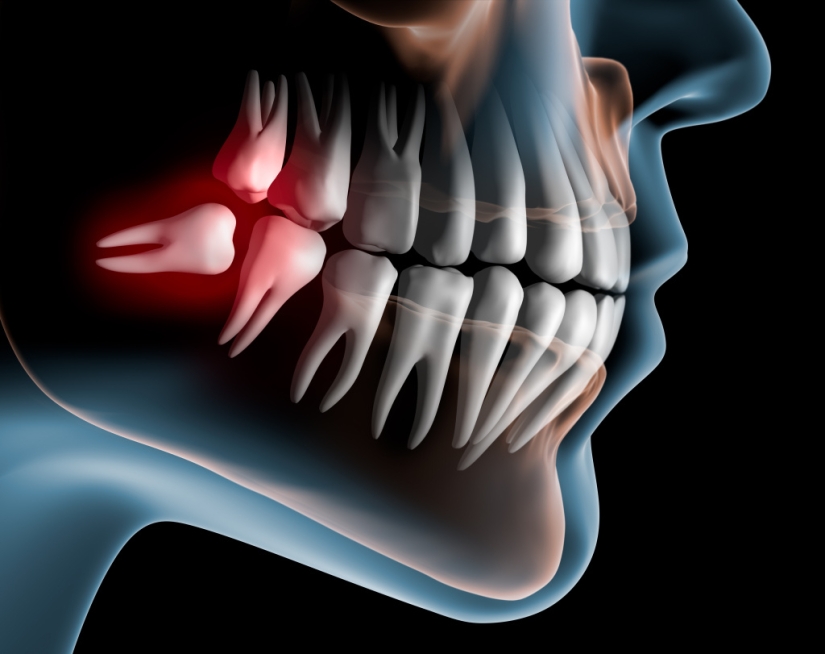

One of the rudiments that are nothing but trouble is wisdom teeth. They are called so because they appear in adulthood. Wisdom teeth once played an important role, as they helped our ancestors effectively chew coarse food. But with the modern diet, their role is minimal. Human jaws have become less massive and are designed for more delicate foods.

However, wisdom teeth continue to grow, causing discomfort and even pain. They do not have enough space in the jaws and grow at an angle. Such teeth are usually removed, and this is completely justified and safe. Modern dentists perform this operation quickly and without consequences.

Everyone is familiar with the condition popularly known as "goose bumps." It is a remnant of a group of tiny muscle fibers that make the hair on the skin stand up. This function is completely useless for modern humans, but it was once vital.

Human ancestors were covered with fur and did not wear clothes. The fur stood up to create an air layer between individual hairs and improve the body's thermal insulation. In addition, the fur standing on end made our ancestors look bigger and could scare off an enemy. People are still sometimes born with fur, which is an echo of our past.

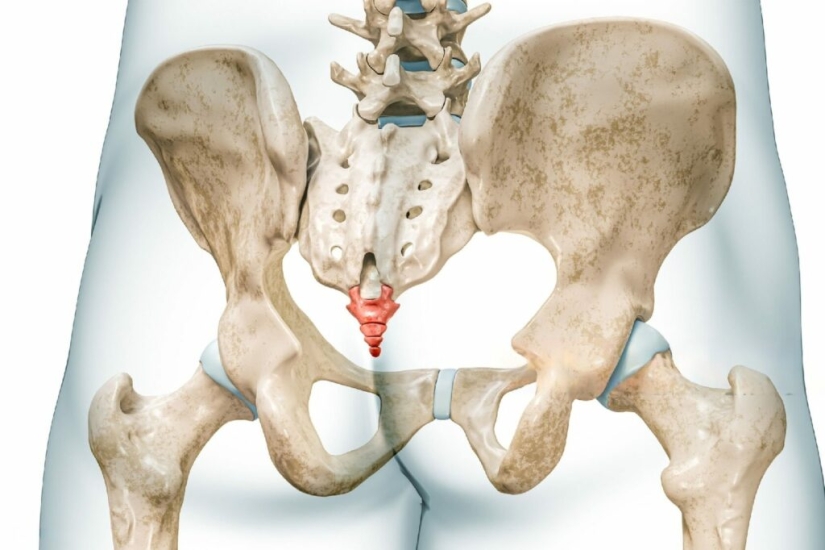

Our spine ends in the coccyx, a collection of fused bones that we inherited from our ancestral tail. These bones lose their function during embryonic development. At one time, primates, the ancestors of humans, had a tail that helped them maintain balance when walking on all fours.

Over time, the need for a tail as a stabilizer disappeared, but coccygeal bones remained in humans. Sometimes children are born with a congenital anomaly - a small tail. Such cases are not associated with genetic mutations, and doctors easily remove the rudimentary organ surgically.

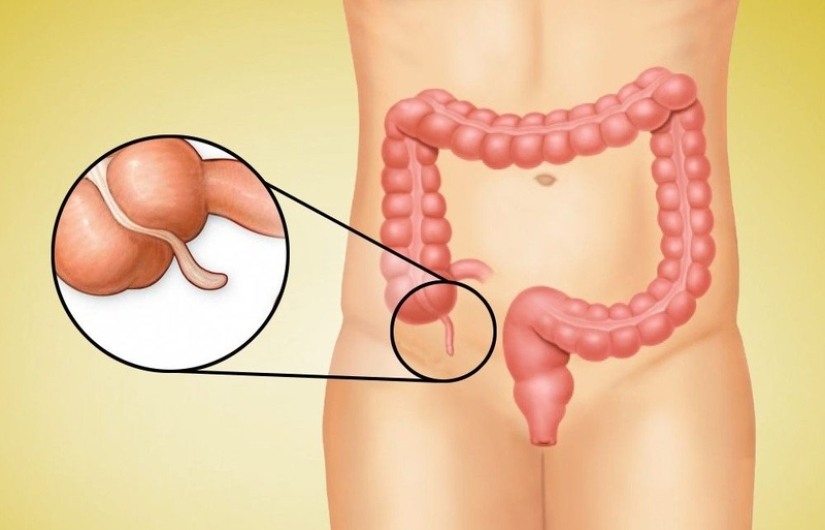

The most famous and at the same time problematic vestigial organ of humans is the appendix. This small intestinal appendage in the past helped to digest coarse food rich in fiber. In many animals, for example in horses, the appendix is of significant size and actively performs its functions. But humans no longer need it, since our diet is dominated by soft and processed food.

The only benefit of the appendix is that it continues to produce bacteria useful for digestion. But inflammation of the appendix is a serious disease that can lead to death if you do not seek medical attention in a timely manner. Therefore, this appendage is more harmful than useful for a person. Removal of the appendix occurs without consequences for the body.

Modern humans rarely have to climb trees, and some avoid such a risky activity altogether. However, for our ancestors, the ability to move along branches was vital. The long palmar muscle (Musculus palmaris longus) is a vestige left over from the times when this skill played a key role.

This muscle used to provide a secure grip and make tree climbing less dangerous. The need for the palmaris longus gradually began to disappear about 3 million years ago, when human ancestors began to move primarily on the ground. With the advent of Homo erectus, or upright man, this muscle lost all function. Today, many people are born without it, which does not affect their physical activity.

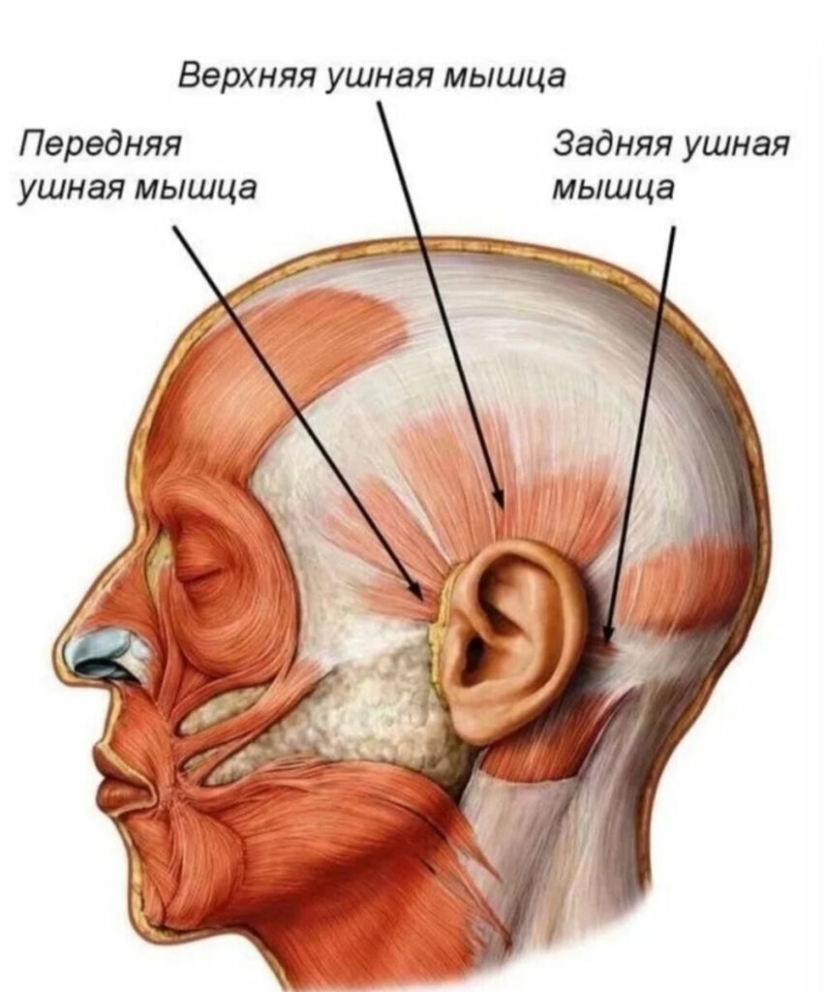

As a child, the ability to move your ears was often admired, but this ability is usually innate and cannot be developed. But for adults, it is not particularly important, because these days this function of the ears no longer has practical significance. But millions of years ago, everything was different: for human ancestors, who lived among constant mortal threats, the ability to move their ears played an important role.

The ear muscles allow you to direct the auricle towards the sound, improving the reception of waves. Many mammals, including domestic cats and dogs, have perfect control over the ear muscles. But it is much easier and more expedient for us to turn our heads, because this movement will not give us away to a predator or potential prey.

The ear muscles are not the only inheritance that our ears have received from our ancestors. About 10% of people have what is known as Darwin's tubercle, a small protrusion on the helix of the auricle. This rudiment is also present in some higher primates. It once represented a pointed tip of the ear, characteristic of monkeys.

This rudiment owes its name to Charles Darwin, the author of the modern theory of evolution. He mentioned this part of the human ear in his scientific work "The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Relation to Sex." The author himself called it the Woolnerian tip, in honor of the British sculptor Thomas Woolner. He was the first to notice this part of the ear when he was working on a sculpture of a forest elf who had pointed ears.

We have told you about only a few organs that humans no longer need. What rudiments do you know?

Recent articles

It's high time to admit that this whole hipster idea has gone too far. The concept has become so popular that even restaurants have ...

There is a perception that people only use 10% of their brain potential. But the heroes of our review, apparently, found a way to ...

New Year's is a time to surprise and delight loved ones not only with gifts but also with a unique presentation of the holiday ...